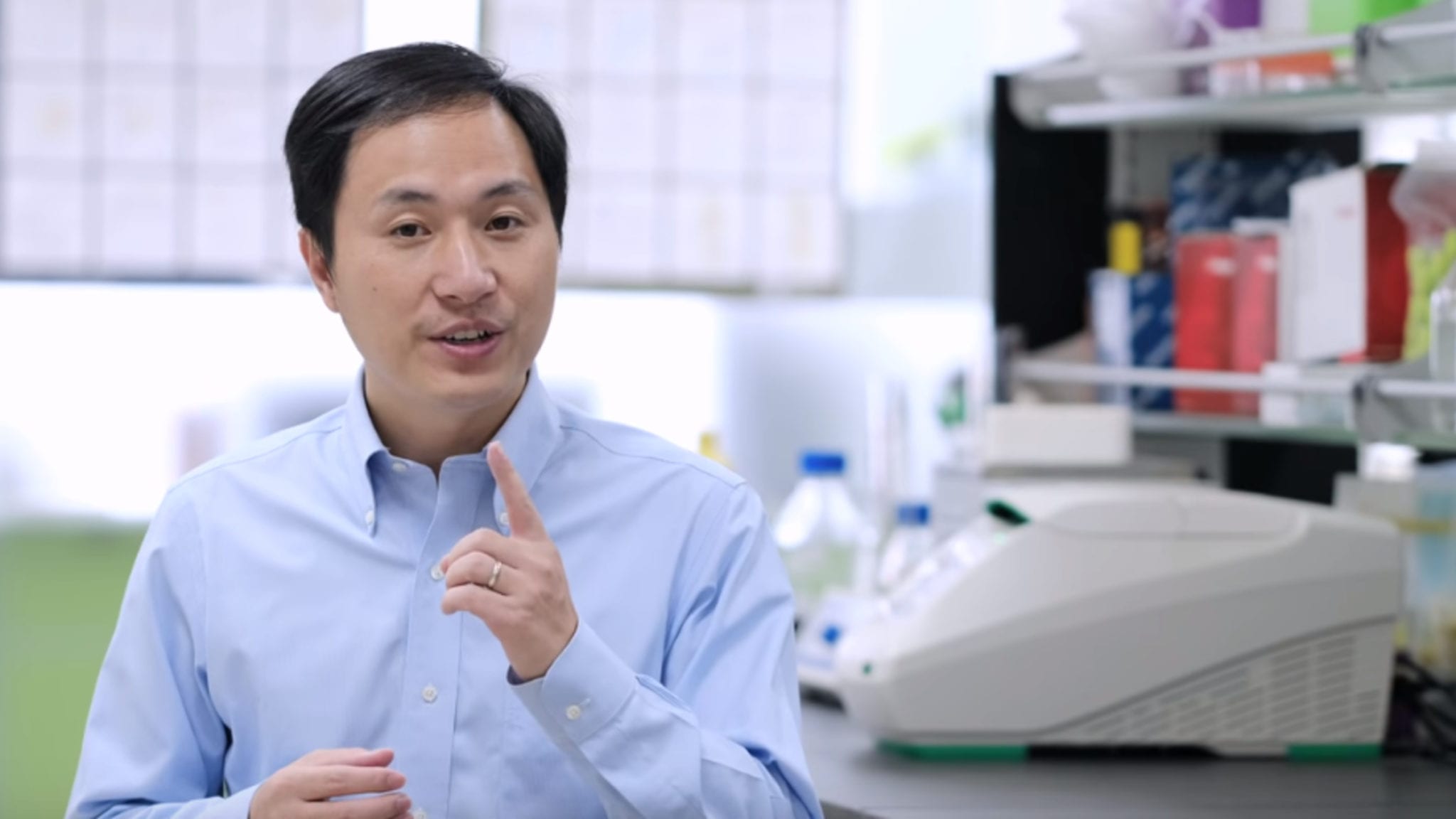

In a landmark first, Chinese scientist claims birth of genetically modified babies — and all hell breaks loose

A Chinese researcher is claiming that he created the first-ever genetically edited babies using CRISPR/Cas9 tools that have now become a common feature in labs around the world. And the news triggered a tempest in scientific circles the world over as researchers who have been using gene-editing tech to refine plants and forge new therapies try to puzzle out the stunning —if true — development featured on YouTube.

Unlock this article instantly by becoming a free subscriber.

You’ll get access to free articles each month, plus you can customize what newsletters get delivered to your inbox each week, including breaking news.