Multivalent mRNA vaccines, I/O 3.0, long-acting HIV drugs: The $46B game is on for the new GlaxoSmithKline

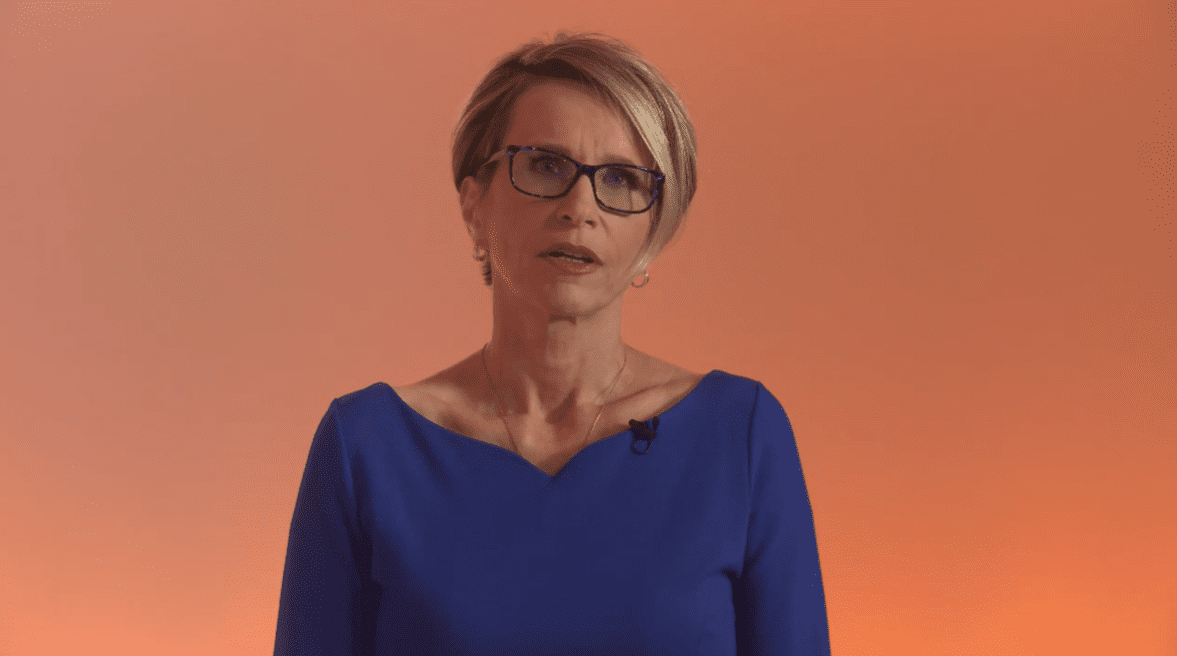

To understand the new GlaxoSmithKline that Emma Walmsley is promising to usher in, one must see through the old GSK.

“We know this has been a company that has perennially disappointed when you look at the first half of the last decade,” the CEO said in one of her final remarks at the long-anticipated investor day.

But after four years of strategic transformation and investment, her top team is ready to take the wraps off a shiny new version of the Big Pharma that, among other things, will strive to deliver £33 billion ($46 billion) in annual sales by 2031. It will start with a planned demerger of the consumer health business into a separate company in the middle of next year, while the new GSK retains a 20% stake as a “short-term financial investment.”

Unlock this article instantly by becoming a free subscriber.

You’ll get access to free articles each month, plus you can customize what newsletters get delivered to your inbox each week, including breaking news.