Cash, chips and talent: Inside Nvidia's plan to dominate biotech's AI revolution

Over the last decade, one tech giant after another has tried to get into healthcare and failed. Amazon’s attempt to reshape costs and delivery sputtered into nothing, IBM’s Watson Health ended in disarray, and Alphabet’s well-funded projects like Verily and Calico have yet to produce anything near the impact of its core tech business.

So why has Nvidia succeeded?

The chipmaker has become the dominant entity in biopharma R&D’s hottest area — using artificial intelligence to design drugs. It’s built a $1 billion-plus revenue stream in health and appears to be winning the argument that this may finally be tech’s healthcare moment — albeit not in the way past challengers thought it would be.

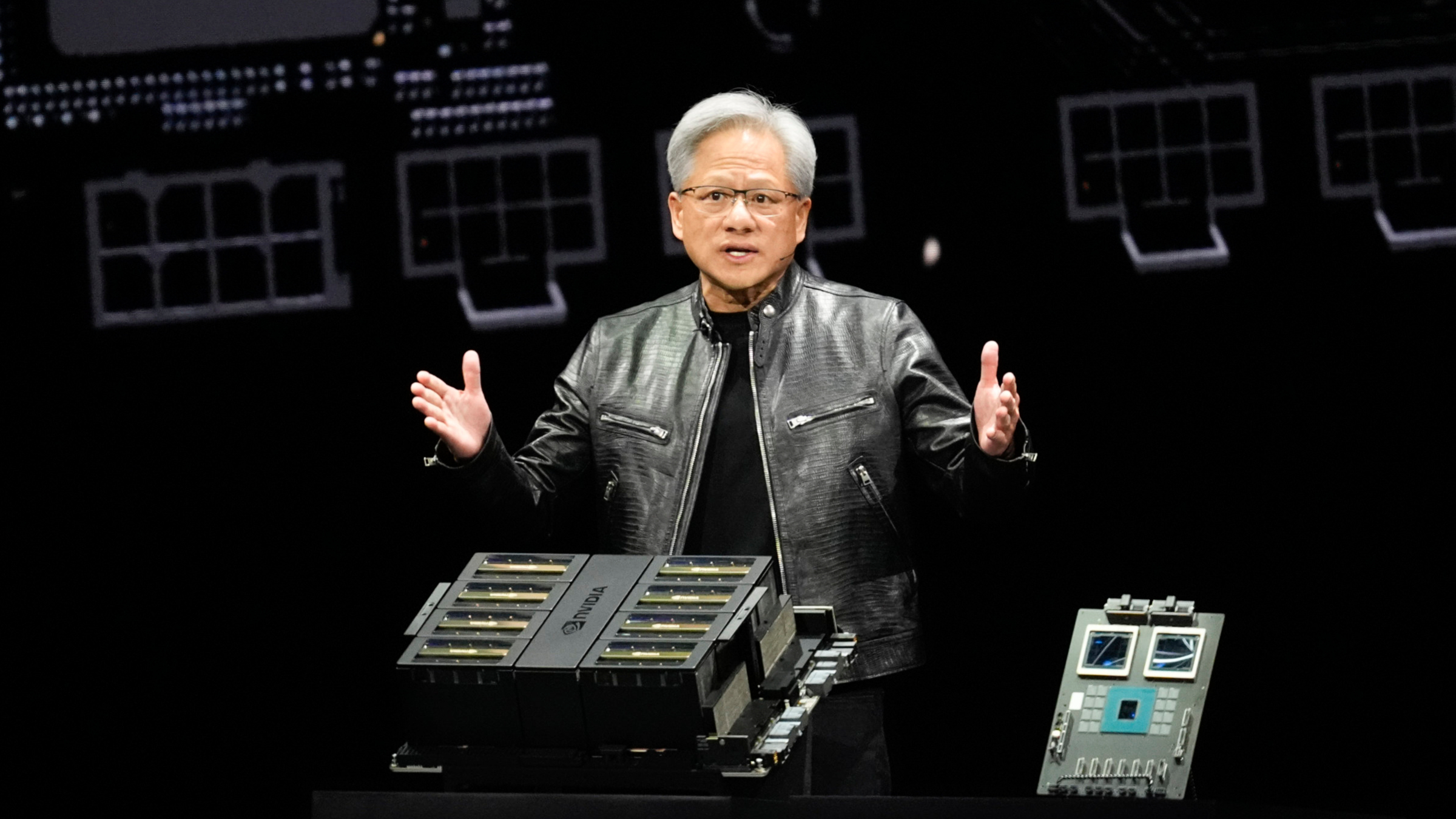

Along the way, Nvidia’s leather-jacket-wearing, vision-slinging CEO Jensen Huang has turned into biopharma’s highest-profile pitchman, selling a future of biology digitized. In addition to the coveted H100 chips at the heart of its business, it also sells software, letting drug companies crib off its own AI talent. And through its corporate venture capital arm, it’s invested in many of biotech’s newest AI startups.

All of which has further intertwined Nvidia with drug developers large and small, adding fuel to Huang’s vision of a growing portion of pharma R&D work flowing through AI — and a growing portion of pharma R&D budgets flowing through Nvidia.

Sean McClain

Sean McClainFor every believer, the company has a share of detractors. Some biotech veterans see an opportunist oversimplifying biology to sell more chips. Others see a visionary hauling a tech-lagging industry stuck on a 90% failure rate into a better future.

“Nvidia is absolutely key to ensuring that AI is ultimately successful in healthcare,” Absci CEO Sean McClain, whose company uses Nvidia’s chips and software, said in an interview. “Even if we have our models, if Nvidia does not exist, AI is not going to make the impact in healthcare at the end of the day.”

From video games to proteins

Nvidia used to be a video game hardware company. It popularized the idea of the GPU — or graphics processing unit — in 1999, which quickly turned into a competitive race with AMD to design the best chip. What pushed Nvidia to the top was software. It designed a new programming language, called CUDA, which turned its chips from video-game renderers into general-computing powerhouses. CUDA allowed Nvidia’s chips to break computing tasks into smaller chunks and then simultaneously work on those jobs. All of a sudden, GPUs weren’t just for video games.

As Nvidia rolled out CUDA in 2006, it noticed certain science groups — not gaming companies — were using 40%, even 50%, of compute cycles on some of the world’s first supercomputing centers. Instead of rendering video games, they were simulating how small molecules and proteins moved and interacted.

Nvidia asked one of those users, Klaus Schulten at the University of Illinois, to speak at one of its first developer conferences in 2010. In front of attendees who mostly came from the gaming world, Schulten guided the audience through wriggling 3D molecular animations, showing how these simulations answered questions like how the swine flu virus resisted the antiviral drug Tamiflu. But the applications were limited, held back by cost and complexity.

Then, in late 2018, Google DeepMind provided a breakthrough when its model, called AlphaFold, won a long-running protein structure prediction competition. In a couple of years, AlphaFold was powerful enough to turn hundreds of millions of strings of amino acids into predicted protein structures.

“The AlphaFold moment convinced us this was possible,” Kimberly Powell, Nvidia’s vice president of healthcare, told Endpoints News in an interview in San Jose.

Kimberly Powell

Kimberly PowellThe chipmaker had already spent years in biology’s weeds, in areas like molecular dynamics, genetic sequencing, and cryo-electron microscopy. By turning amino acid sequences into highly accurate 3D structures, AlphaFold led Powell to imagine what else could be possible.

“Once you can represent something in a computer, you can start building models,” Powell said. “Once you have models, you can start learning more about their interactions. This, to me, is a new dawn of computer-aided drug discovery, moving into many more areas than just the molecular dynamics simulations.”

In fall 2022, Nvidia launched BioNeMo, a software service offering access to dozens of AI models, including AlphaFold. Other models can simulate molecular docking with DiffDock, generate small molecules with MolMIM or proteins with RFdiffusion, or predict how strongly a molecule binds to a protein with NeuralPLexer. Over 100 biopharma customers are now using BioNeMo, and Powell sees this as just the start.

Hardware remains the heart of Nvidia’s business. It’s currently building supercomputers for the Novo Nordisk Foundation in Denmark and for Amgen in Iceland — tapping into the latter’s massive genetic trove through its deCODE genetics subsidiary. But its software, tailored to the drug industry to put that compute into practice, is becoming a huge focus.

Philipp Lorenz

Philipp Lorenz“They know the industry so well that I never talk to them about chips, which is kinda weird,” said Philipp Lorenz, chief technology officer of Basecamp Research, a London-based startup generating a massive database of protein sequences from all types of organisms.

Part of Nvidia’s software play is based on the fact it has some of the top AI talent that pharma can’t hire. A mix of pay, culture, and resources has lured the best engineers to richly funded AI startups like OpenAI and Anthropic or to legacy tech giants like Google and Meta, said Dylan Reid, a venture capitalist at Zetta Venture Partners. Drugmakers are “not getting close” in trying to attract top AI talent now, Reid said.

Nvidia fills that gap, with its own engineers taking the lead on optimizing, training and fine-tuning models for drug companies.

“These pharma companies, they’re not OpenAIs,” Powell said. “That’s not the kind of people that they have on staff.”

In its latest offering, Nvidia introduced what it calls microservices last month. These are AI models ready to use out of the virtual box, with Nvidia charging $4,500 per GPU per year or $1 per GPU per hour to use these services. Nvidia says a pharma company can start using these models within minutes, requiring no AI expertise of its own. It lets drug companies do what they know best, while Nvidia provides its core strength — compute power and engineering know-how.

“Jensen is continuously thinking about the future and will make investments in the present even if it costs him bottom line to make the future better,” Vijay Pande, a biotech VC at Andreessen Horowitz, said in an interview. “That’s why he is where he is now, and why Nvidia is where it is now.”

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang during his 2024 keynote address (Eric Risberg/AP Images)

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

Huang opened this year’s Nvidia developer conference with a two-hour talk in front of over 10,000 attendees packed into the SAP Center in San Jose. “Unbelievable new capabilities will be invented,” Huang said in pitching AI as an industrial revolution spanning virtually every industry.

And he has compared the possible future of drug discovery to the evolution of designing chips, which went from a high-error rate, complicated process, to in silico design with virtually no errors.

“Biology is a billion times harder than physics-based in silico design of a chip, which is saying a lot. But I think it’s inevitable that we’re going to get there,” Recursion CEO Chris Gibson said in an interview. “It’s just a question of who, what, when, and how.”

Chris Gibson

Chris GibsonThese kinds of lofty hopes have created plenty of doubters, especially among industry veterans who have seen similar Silicon Valley dreams fizzle before.

Keith Hornberger, a veteran medicinal chemist, described Huang’s view as “wildly optimistic” and “hopelessly naive.” Even ardent backers of AI in biology have called for the field to tamp down the rhetoric, such as Schrödinger’s CEO warning of “dangerous” levels of AI buzz last summer, or insitro CEO Daphne Koller calling the current hype “potentially destructive.”

Ultimately, the only metric that truly should matter is how many real medicines are developed — a milestone the field hasn’t yet cleared. Recursion expects its first Phase 2 readouts later this year, with its CEO comparing the moment to SpaceX firing off its first rockets.

“People are launching things,” Gibson said. “There are going to be failures, but ultimately, we’re all figuring out how to put the pieces together, and when it starts working in 12 months or 36 months or whatever, a few years, it’s going to be an entirely different industry.”

The gold rush

All the while, Nvidia keeps growing deeper roots. Andrew Gostine, CEO of a hospital automation startup called Artisight, said his company has tried other chipmakers, even as Nvidia has invested in Artisight, but found the effort to optimize models and fit them into the startup’s ecosystem a “huge pain.”

Andrew Gostine

Andrew Gostine“The amount of money I would have to spend to buy AI talent to do that optimization, Nvidia gives it to you for free — if you buy their super-expensive GPUs,” he said while presenting at last month’s Nvidia developer conference.

Artisight is one of more than 20 companies that Nvidia’s two-year-old corporate VC arm has invested in — another way the chipmaker has deepened its healthcare presence. The group doesn’t have a set amount of money to put to work each year, or many directives beyond finding interesting startups working on big goals and using Nvidia’s chips.

A few months before its San Jose spectacle, Nvidia jointly held a separate, much smaller event at the JP Morgan healthcare conference. On a rainy January night, biotech executives and investors packed a room to hear Huang’s vision of reinventing one of the most failure-prone businesses on earth. He spoke of a miraculous AI revolution poised to reshape drug R&D.

“We deeply believe that this is going to be the future of the way that drugs will be discovered and designed,” Huang said.

Early evidence is trickling in that Huang may be right — or right enough to keep winning customers. Amgen, an early user of Nvidia’s software, says it has boosted the likelihood of an antibody program reaching the clinic from 50% to 90%, while shortening the typical research timeline from two years to nine months. Genentech recently launched a study testing a lung disease drug candidate in inflammatory bowel disease, based on unexpected connections between the two revealed by machine learning. Startups like Generate:Biomedicines and Iambic are now in the clinic with drugs taking advantage of some of these newer AI models.

In a blunt symbol of where the money is in biotech right now, the January JP Morgan event was hosted at the San Francisco Mint. The 150-year-old building was constructed to serve the booming needs of the California Gold Rush, turning gold nuggets into cash. Nvidia is eagerly bringing pharma into the next frenzy.

“Please, if you have a hard time with computation or artificial intelligence, send us an email,” Huang told the JPM crowd. “We’re here for you.”