Back to the future: From target-selective drug design to AI-enabled polypharmacology

CNS drug discovery is being thrown back to the 50s, when the drugs’ phenotypic profiles alone led to the first blockbuster drugs for mental disorders. PsychoGenics’ SmartCube® platform allows us to use AI on a journey back to phenotypic drug discovery.

AI in drug discovery and development

AI applications range from target discovery, target-based drug design, toxicity predictions, manufacturing, and clinical trials, to name a few. Some AI-based target-driven drug discovery efforts focusing on known proteins have proven successful, supported by the existence of good quality data [1, 2]. For complex CNS pathology, however, the target is either unknown or there is no unique target that can provide the necessary relief. At PsychoGenics, we tackle CNS complexity head on, predicting efficacy for novel polypharmacological, unknown mechanism of action, or target-driven compounds, using a target-agnostic Al-enabled drug discovery platform.

CNS target-selective drug design fails. Complex living systems function is supported by the interaction of multiple overlapping and interacting pathways, which achieve homeostasis through redundancy and feedback loops. Thus, modulating a single target can trigger compensatory mechanisms by other pathways, rendering the treatment ineffective. An unjustified desire to create molecules with the highest single-target selectivity, compounded with the human tendency to simplify complex systems, desire to understand individual disease elements, and ignorance of physiology and CNS function has led to failures in the clinic[3]. Indeed, of 1,144 FDA-approved small molecule drugs, only 123 (~11%) were discovered by target-based drug discovery and 1,021 (~89%) by phenotype-based drug discovery approaches[4]. CNS disorders present with multiple risk factors and are unlikely to arise from a single element, and therefore phenotypic drug discovery for polypharmacological compounds can lead to novel and effective treatments. Here we elaborate on the way AI-enabled platforms can be used for target-agnostic de novo drug discovery.

AI-enabled phenotypic drug discovery

Whereas drugs for mental disorders have been used around the world for centuries (e.g. reserpine and psilocin), Western psychopharmacology was revolutionized in the 50s as scientists observed that non-psychiatric drugs had beneficial effects on psychiatric symptoms[5]. The discovery of chlorpromazine, and soon thereafter imipramine, opened the road to the synthesis of novel compounds and pharmacological treatments for mental illnesses[6]. These drugs are an example of complex polypharmacology, as they act at many targets in the CNS (dopaminergic, serotonergic, etc), discovered in a target-agnostic phenotypic manner.

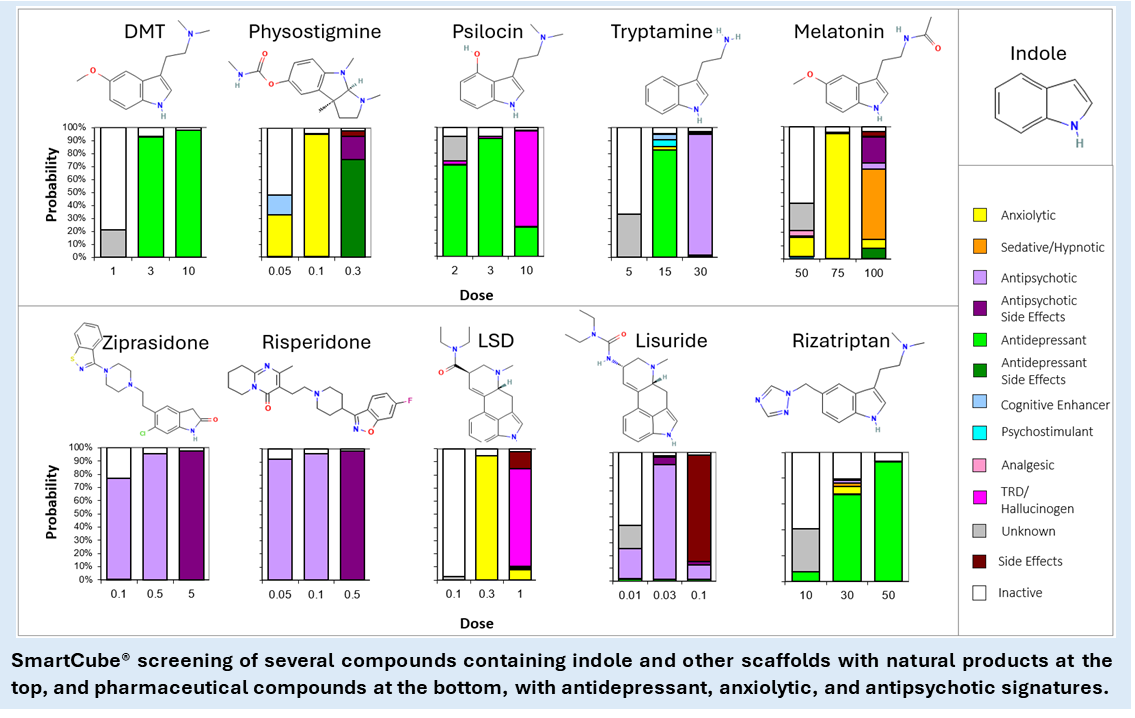

Privileged structures for polypharmacology. Through trial-and-error, natural selection leads to variations in the characteristics of receptors and neurotransmitters, giving onto to the creation of privileged scaffolds, basic core structures common to a series of biologically active molecules. As an example, take the indole scaffold, present in natural products and CNS molecules (e.g., reserpine, physostigmine, psilocyn, tryptamine, serotonin, melatonin, harmine, and DMT) and countless pharmacological compounds (e.g., molindone, sumatriptan, ondansetron, pindolol, ziprasidone, risperidone, and LSD)[7, 8]. Privileged scaffolds serve, therefore, as the basis of polypharmacological series of compounds with different functions, thanks to, sometimes, subtle changes or additions to the core structure.

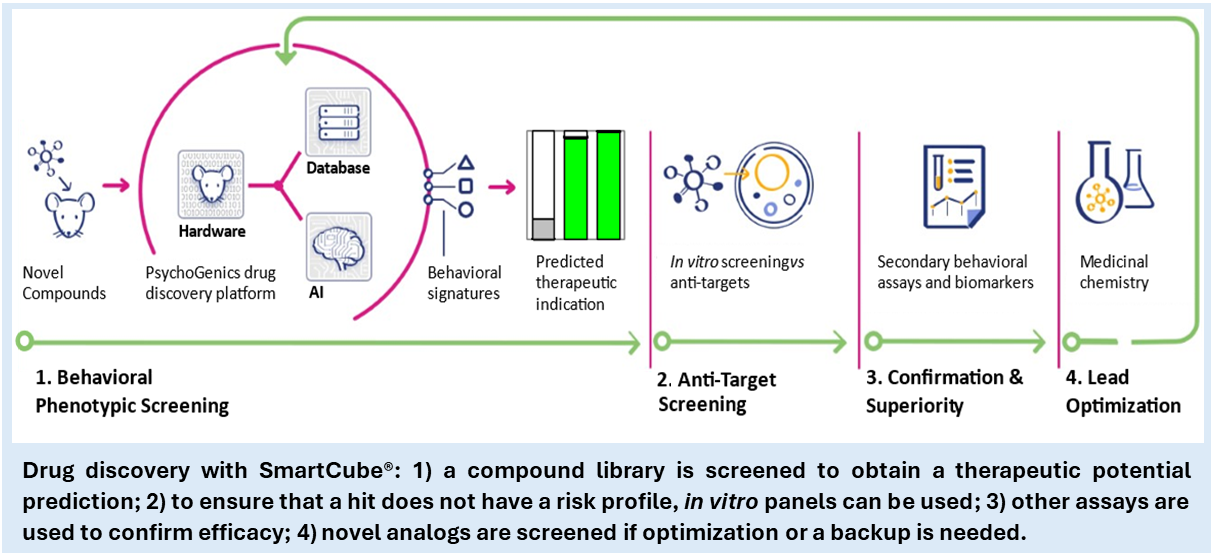

AI-enabled phenotypic approach. Designing compounds in silico solely based on structure and ligand data is difficult[9], but becomes a near impossible feat when polypharmacology is the goal, as the optimization of PK/PD relationships at several targets at once cannot be achieved. This can be solved by a comprehensive in vivo screen sensitive to polypharmacology, enabling rapid predictions about therapeutic efficacy. This strategy is captured in a few available phenotypic assays, often using zebrafish, C. elegans, or other “simple” organisms. PsychoGenics uses the more complex behaviors of mice in the SmartCube® platform, to capture drugs’ therapeutic profiles for depression, psychosis, and other indications.

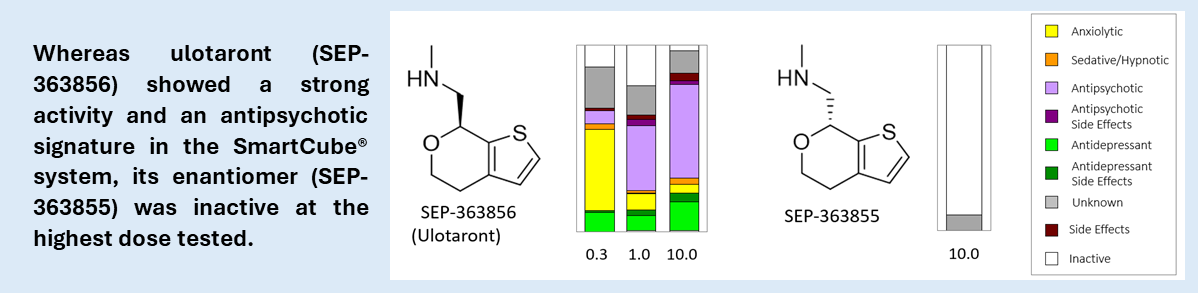

PsychoGenics’ SmartCube® behavioral screening platform[10] is based on machine learning classification of compounds’ behavioral profiles in mice captured through 3D computer vision. Machine learning classifiers are trained using marketed drugs to define therapeutic profiles (antipsychotics, anxiolytics, analgesics, mood stabilizers, treatment-resistant depression antidepressants, and others), in a target-agnostic manner. The platform can be used to characterize a novel compound, perform structure-activity relationship, test a candidate in an animal model of disease, or compare potency of different enantiomers, to name a few applications.

Screening compounds and libraries using SmartCube®

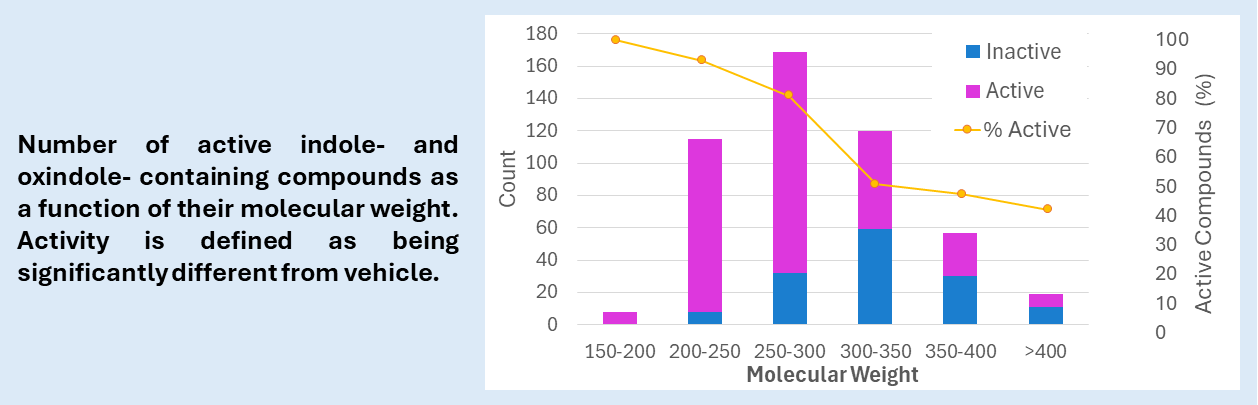

We have screened thousands of compounds from commercial or partnered libraries, including 489 with indole and oxindole cores. Whereas a diverse Lipinsky-compliant small molecules library has an activity rate between 30 and 50%, choosing these scaffolds and focusing on compounds with low molecular weight brings the activity rate higher than 80%. Historically, we have shown that design of compounds around a privileged structure combined with our rapid phenotypic therapeutic prediction can deliver a polypharmacological development candidate in fewer than 300 compounds. This approach to screening and lead optimization delivers a candidate at a fraction of the cost and time associated with targetbased discovery.

From SmartCube® to the clinic. Our most advanced compound, developed in collaboration with Sumitomo Pharma, is Ulotaront, an antipsychotic with agonistic action at the 5HT1A and TAAR1 receptors, D2 sparing[11] discovered empirically using SmartCube®. Ulotaront is in several Phase II and III clinical trials, after promising results in Phase II trials leading to a Breakthrough Therapy Designation from the US FDA for the treatment of schizophrenia. Specifically, ulotaront was effective in countering positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia with placebo-like side effects, all predicted preclinically.

New opportunities partnering with PsychoGenics

Today’s innovative environment presents numerous partnering opportunities where PsychoGenics’ SmartCube and other AI-enabled platforms can be utilized to identify compounds with potential to treat neuropsychiatric disorders. SmartCube® can of course also be used to screen target-based designer drugs, and, not only small molecules, but also small peptides. Using SmartCube® for Psylin, a joint venture with Amylin Pharmaceuticals, we screened a library of small peptides leading to the discovery of several peptides, including a GLP-1 agonist with a mixed anxiolytic and antidepressant potential in addition to cognitive enhancing activity and the expected weight-loss effect. New potential libraries include PROTACs, molecular glues, combinations, ion channels, membrane stabilizers, intrinsically disordered proteins, biomolecular condensates, Mas-related GPRCs, and mitochondrial, glymphatic system, neuroinflammatory, and gut-brain axis targets.

PsychoGenics’ proposal. The complex interplay among multiple neurotransmitter systems, particularly in the context of the pathophysiology of CNS diseases where the underlying biological mechanisms are often poorly understood, presents a formidable challenge for to the development of new drugs for psychiatric disorders. The most effective drugs used in the clinic typically exhibit polypharmacology, modulating multiple targets simultaneously. PsychoGenics platforms can assist in several aspects of the drug discovery process, from compound screening, SAR, and lead optimization to facilitate the discovery of novel polypharmacological treatments.

To learn more about PsychoGenics’ commitment to drug discovery innovation visit https://www.psychogenics.com.

References

- Keshavarzi Arshadi, A., et al., Artificial intelligence for COVID-19 drug discovery and vaccine development. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 2020. 3: p. 65.

- Chávez-Hernández, A.L., E. López-López, and J.L. Medina-Franco, Yin-yang in drug discovery: rethinking de novo design and development of predictive models. Frontiers in Drug Discovery, 2023. 3: p. 1222655.

- Stefan, S.M. and M. Rafehi, Medicinal polypharmacology: Exploration and exploitation of the polypharmacolome in modern drug development. Drug Dev Res, 2024. 85(1): p. e22125.

- Sadri, A., Is target-based drug discovery efficient? Discovery and “off-target” mechanisms of all drugs. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2023. 66(18): p. 12651-12677.

- Lopez-Munoz, F., et al., History of the discovery and clinical introduction of chlorpromazine. Ann Clin Psychiatry, 2005. 17(3): p. 113-35.

- Chow, W.S. and S. Priebe, Understanding psychiatric institutionalization: a conceptual review. BMC Psychiatry, 2013. 13: p. 169.

- de Sa Alves, F.R., E.J. Barreiro, and C.A. Manssour Fraga, From nature to drug discovery: the indole scaffold as a ‘privileged structure’. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry, 2009. 9(7): p. 782-793.

- Stempel, E. and T. Gaich, Cyclohepta [b] indoles: a privileged structure motif in natural products and drug design. Accounts of chemical research, 2016. 49(11): p. 2390-2402.

- Stefan, S.M. and M. Rafehi, Medicinal polypharmacology: Exploration and exploitation of the polypharmacolome in modern drug development. Drug Development Research, 2024. 85(1): p. e22125.

- Brunner, D., Gondhalekar, V., Leahy, E., LaRose, D., Ross, W.P., Method for predicting treatment classes using animal behavior informatics, USPTO, Editor. 2009, Carnegie Mellon, University Psychogenics Inc: U.S.

- Dedic, N., et al., SEP-363856, a Novel Psychotropic Agent with a Unique, Non-D(2) Receptor Mechanism of Action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2019. 371(1): p. 1-14.