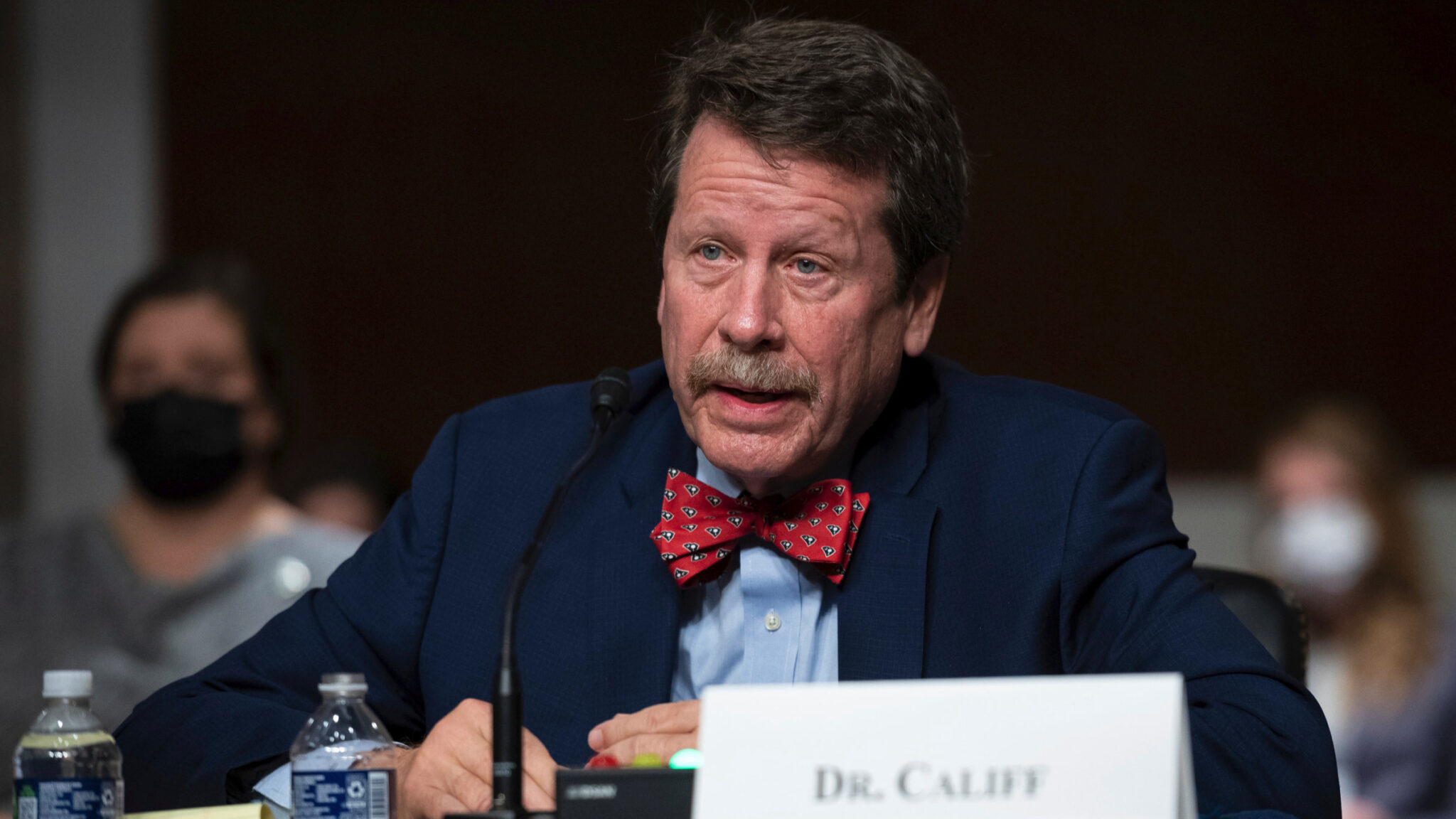

Robert Califf, FDA commissioner nominee (Graeme Sloan/Sipa USA/Sipa via AP Images)

Califf on accelerated approvals: Companies need to do more work before FDA says OK

As he awaits a tight Senate vote, Rob Califf, President Joe Biden’s nominee to be the next FDA commissioner, is signaling where the agency may …

Sign up to read this article for free.

Get free access to a limited number of articles, plus choose newsletters to get straight to your inbox.