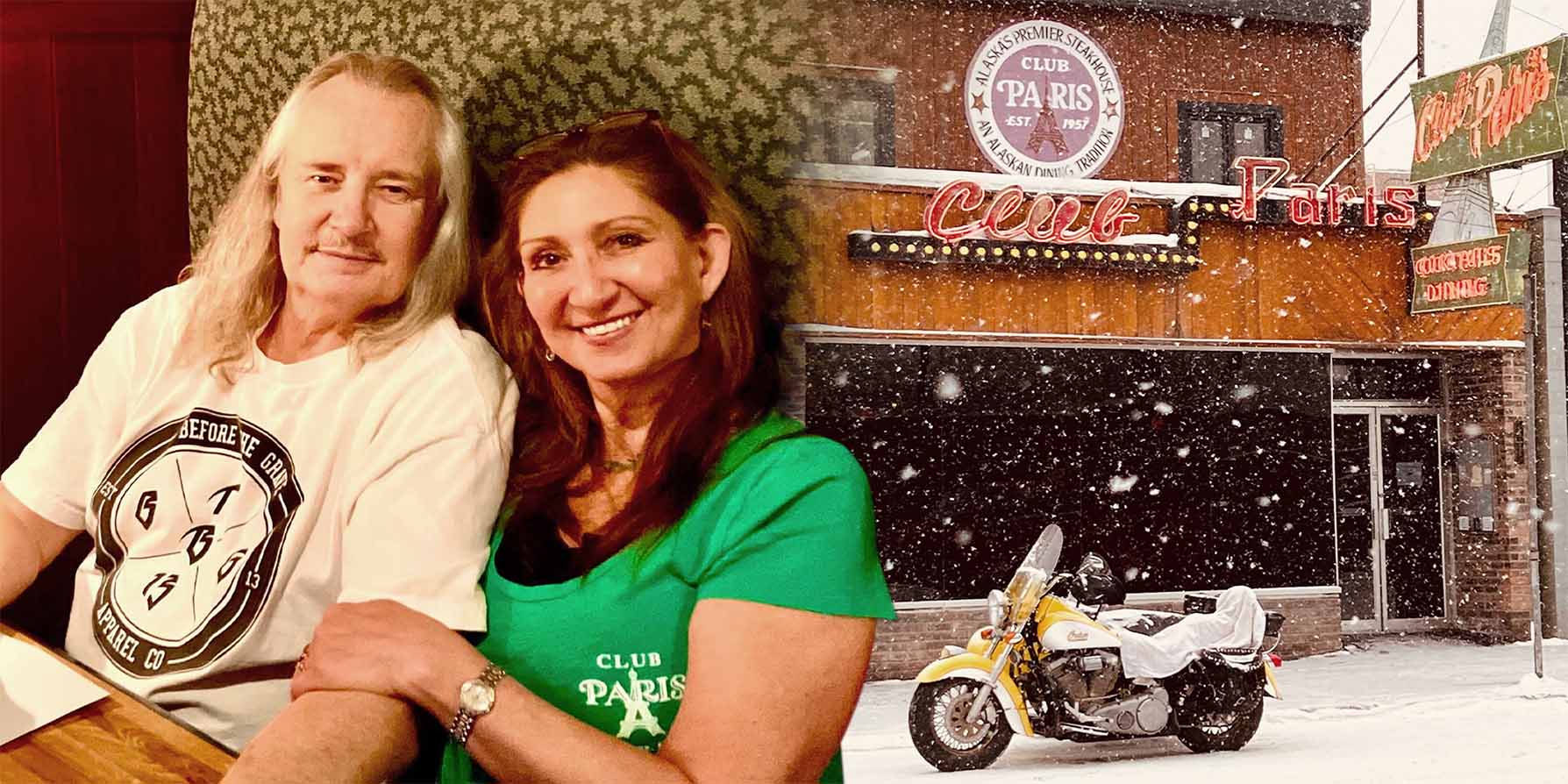

Scott Selman, his wife and their restaurant, Club Paris

Covid vaccines and drugs are free. But for many immunocompromised patients, protection comes at a cost

To tell the truth, Scott Selman didn’t mind the pandemic at the beginning. He was a solitary man who spent his weekends on home construction …

Sign up to read this article for free.

Get free access to a limited number of articles, plus choose newsletters to get straight to your inbox.