Escaping an improbable upbringing, Greg Verdine places his biggest career bets in drugging the ‘undruggable’

In another world, Greg Verdine would still be building boats and tearing apart car engines in his New Jersey front yard.

Verdine, who started ditching school at age 7 to work on home projects at the insistence of his father, improbably built a career as a Harvard University professor, serial biotech entrepreneur and iconoclast. He’s gone to war with the industry’s conventional wisdom that drugs simply can’t reach some disease-causing proteins because of their shape.

In his career-long obsession to drug the undruggable, a phrase he says he coined, he was denied grants and lost control of past ventures. He left his longtime spot at Harvard to fulfill his quest and lead two startups, FogPharma and LifeMine Therapeutics, that have combined to raise over $600 million. Fog announced Monday that it had dosed the first patient with its lead drug candidate, targeting a common driver of cancer that’s also a poster child for those impossible-to-hit proteins.

“This is shameful that we just say, ‘Oh they’re undruggable,'” Verdine said in an interview with Endpoints News. “That’s capitulation, that’s pathetic. That’s not a proud industry.”

Leaders and scientists who’ve worked with the 63-year-old describe a brain overflowing with ideas coupled with a magnetizing ability to pitch his vision. But they also point out that the coming years will determine whether he can leave a lasting mark on biotech.

“It always felt like a huge risk to hire Greg as CEO,” said Rick Klausner, the former National Cancer Institute director and a friend of Verdine’s for decades who sits on Fog’s board. “Greg has this endless curiosity. There was a real concern he was a starter, but not a finisher.”

But Klausner added that Verdine has shown the ability to grow in the CEO role.

“These are Greg’s biggest bets,” Klausner said of the new startups. “He could have just been publishing about this stuff, but Greg really wanted to make real drugs that go into people and solve problems.”

***

Growing up in the rural Pine Barrens of New Jersey, education was not a priority for the Verdines.

His father dropped out of school in the ninth grade and worked at a heavy-equipment company. Verdine’s three brothers followed similar paths into blue-collar trades.

Verdine’s own life was upended when he was 5. His father dived into a neighbor’s pool and landed on his neck, leaving him quadriplegic and unable to build with his hands.

So he turned to his son. Verdine learned to weld as a 7-year-old, and his dad started keeping him home from school to work on increasingly ambitious projects. The two built a 12-foot sailboat, constructed a wheelchair lift for a van, reassembled Chevrolet Corvair engines, and even renovated a 42-foot Chris-Craft boat blocked up on their front yard.

His mother had different ideas. After she found out he was missing school, she convinced the high school’s assistant principal to take him in.

Despite a poor attendance record, Verdine had a knack for school. His guidance counselor was impressed by his SAT score, but Verdine wasn’t planning to go to college. He thought he got someone else’s mail by mistake when he opened an acceptance letter from Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia. When a second letter arrived with a full scholarship offer, he knew something was up.

“My high school guidance counselor had gone behind my back, got me into college and got me a scholarship because he knew I couldn’t afford it,” Verdine said.

At college, Verdine found his childhood tinkering translated to the lab. Pushing a chemical reaction was like tightening a bolt on an engine block.

“I’ve worked with a lot of scientists, and he’s really in the top 1% as far as creativity, intelligence and ability to go around issues,” said Elias Zerhouni, a former NIH director who worked with Verdine while running R&D at Sanofi.

Verdine rapidly moved from Saint Joe’s to Columbia University and finally to a junior faculty spot at Harvard in 1989. The $57,000 salary in those early years was his first taste of life-changing money compared to his backwoods childhood, and it would soon be coupled with an eye-opening trip to Switzerland.

***

It was the mid-1990s and Verdine was there to see cutting-edge research by Hoffmann-La Roche. The pharma giant had built the first-ever automated screening system, testing its entire library of over one million compounds against several dozen top targets. The end result was sobering: zero hits.

“That was the first time I heard the term undruggable,” Verdine said.

He saw a consensus emerge, with researchers characterizing proteins by druggability. And as more and more of his peers started to use that language, Verdine rebelled.

“Greg’s brain is not at all bounded by the possible,” said Barbara Weber, CEO of Tango Therapeutics and a board member of Fog. “He doesn’t care. He doesn’t even think about whether something might be viewed as possible to somebody else.”

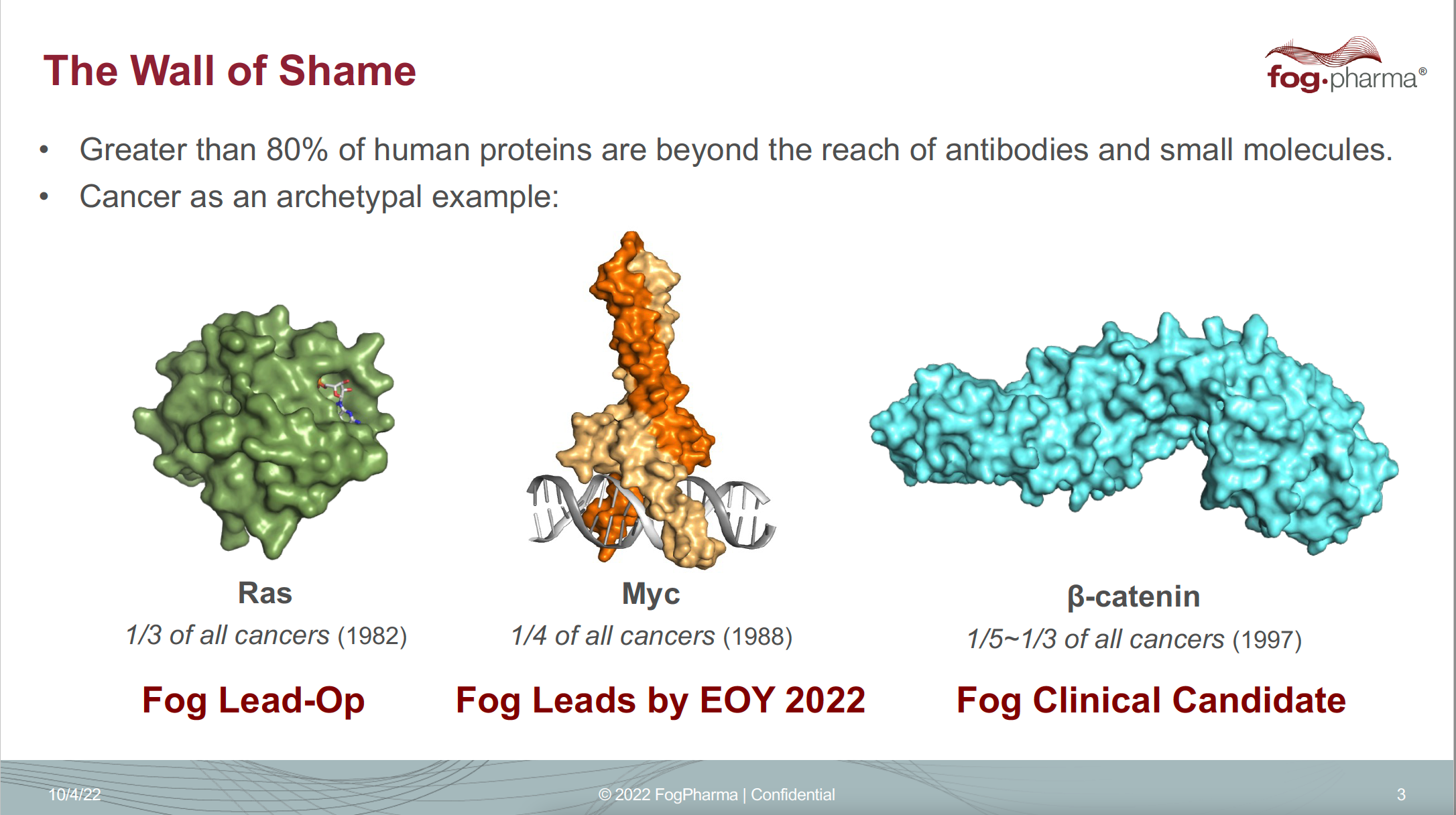

Verdine says he coined the phrase “drugging the ‘undruggable’” and started lecturing on it in the early 2000s. He traveled from conference to conference flashing a provocative slide entitled “The Wall of Shame.” Like a most-wanted fugitive list, it showed the mugshots (or molecular structures) of three major cancer-driving proteins: beta-catenin, Ras, and Myc. Despite playing a major role in cancer, they were written off as too hard to target.

Verdine has presented a version of this “Wall of Shame” slide for years, highlighting a few so-called undruggable cancer targets.

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

***

Verdine set his lab on the problem. Christian Schafmeister, now a chemist at Temple University, joined to turn peptides, the building blocks of proteins, into drugs. While Verdine says he never got an NIH grant approved for the research, they published their first work in 2000.

In 2001, that peptide research became Aileron Therapeutics, one of the first companies Verdine started. But very quickly, he learned the value of control. He wanted a scientist to be in charge; the company hired a CEO with a legal background.

“It’s the only company that I really ever severed ties with early on because of a fundamental disagreement with the philosophy of the investors,” Verdine said.

Verdine says Aileron made common biotech mistakes: narrowing its focus on its first program at the expense of the platform and rushing to go public. Aileron now teeters on survival, as its stock has plunged over 98% since going public in 2017 and terminating that drug’s development earlier this year.

Verdine found more success in other ventures, like Gloucester Pharmaceuticals, which won an FDA approval and was bought by Celgene for about $450 million, paying Verdine about $5 million. In 2010, he co-founded Warp Drive Bio, which started to develop drugs targeting Ras, a “Wall of Shame” cancer-causer, when he ran the biotech from 2013 to 2015.

But he kept hitting Harvard’s limits, having to leave Warp Drive to return to the university after maxing his sabbatical. Revolution Medicines acquired Warp Drive a few years later, and has started testing some of those Ras drugs in the clinic. But he was feeling the limits of the scientific founder role.

“I wanted more control,” Verdine said. “If I was going to give up my faculty job at Harvard, I wanted the time to make it work.”

***

Verdine is now taking that bigger swing, starting FogPharma in 2016 to develop more peptide drugs. In his style, Fog is pursuing the undruggable mantra, which has become a common industry refrain that Verdine insists few actually follow.

“Most of them are bullshitters,” he said. “It’s more like redrugging the druggable.”

Fog picked a worthy first foe: beta-catenin. Despite being found in most cases of colorectal cancer, half of prostate cancers, and about a third of melanoma cases, no drug company has been able to drug the protein.

Beta-catenin’s notoriety starts with its shape, which is the nightmare of chemists. Proteins that are easy to drug have nooks on their surface. Molecules slide into those crevices, like a plug going into a socket. Beta-catenin lacks those pockets and is flatter than most proteins.

On top of its flatness, beta-catenin is nestled inside cells. Antibody drugs look for proteins on the surface of cells, as they can’t pass through the cell membrane.

All told, beta-catenin is like a locked treasure chest without a keyhole to open it, buried under a sheet of cement. The industry’s typical tools — small molecules and biologics — couldn’t crack it, so pharma companies settled for related, more accessible targets. Those programs were routinely abandoned with toxicity issues or mediocre clinical results, leaving beta-catenin untouched for decades.

Verdine believes Fog can crack the protein by pairing the special shape of his peptides with cutting-edge biology. It goes back to early research with Schafmeister, shaping the peptides into spirals. They copied that shape from cell-membrane proteins that are also helical. The coils hide the peptide from cells, tricking them into letting the drug inside. Once inside, a peptide has greater binding powers than a small molecule to cling onto beta-catenin.

Fog also leaned into cutting-edge research, working with the Broad Institute to probe beta-catenin for vulnerabilities, using the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out genes and observe the effects on cancer. Around 2019, that research led Fog to abandon a program and start over, as it found its initial target, an interaction site with another protein called BCL9, wouldn’t help fight cancer.

Friends like Klausner were supportive — but skeptical. “I thought he’d be able to find things that bind, but I was very skeptical that he could turn them into drugs,” he said.

By digging deep into beta-catenin, Fog wound up with over 25 possible places its peptides could bind to the protein, in contrast to conventional wisdom that it lacked anywhere to land a drug.

“It’s chock full of targetable sites, but only one is the right one,” he said.

Many biotech boards would see these challenges and demand a change in strategy to less risky research. But Verdine built Fog differently in 2016, turning to friends instead of VCs for greater control. About 60% of Fog’s $11 million seed round came from high-net worth friends, while the other 40% came from WuXi’s corporate investment arm and Deerfield Management. One of those friends and investors, Jeffrey Leerink, suggested the name: Fog, short for Friends of Greg.

“What you learn after starting enough companies is the founding architecture of a company stays with it, at least until it’s public,” Verdine said. “If you have a bastard birth, you end up with a bastard teenager and a bastard adulthood. I didn’t want a bastard birth.”

Taking on the CEO spot also brought Verdine’s run at Harvard to a close. The university didn’t want its professors to be full-time CEOs, and Verdine left Harvard in 2020 to run his biotechs.

After years of grinding in the lab, Fog’s drug is now in the clinic. Verdine believes they have found the right keyhole, with a transcription factor called TCF4 that acts like an “executioner” in setting off beta-catenin’s cancer-driving behavior.

Skeptics like Klausner have turned into believers, raving over preclinical results, some of which were presented earlier this year. An investment fund run by Klausner and the billionaire Yuri Milner led Fog’s $178 million Series D last year. Verdine will also hand over the CEO role in a few days to Mathai Mammen, formerly Johnson & Johnson’s R&D head and a teaching assistant of Verdine’s in the early 1990s. Early clinical results are expected in the first half of 2024.

***

Much of Verdine’s biotech legacy will be written in the coming years. Clinical data will decide what’s real and what remains theoretical. Verdine is about to get a lot of those results, with Revolution’s Ras inhibitors and Fog’s beta-catenin blocker in the clinic.

Peptides are already having a quiet resurgence, driven by weight loss drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro, which bind to receptors sitting on the surface of cells. Fog could break new ground if its peptides work inside cells.

“The whole field is waiting for an approved peptide-based drug targeting an intracellular protein,” said Tom Grossmann, a German chemist who worked in Verdine’s lab as a postdoctoral researcher and now runs his own lab in Amsterdam.

For Verdine, who turns 64 in a few days, he says he expects to not slow down until he’s in his 70s, health permitting. The ideas haven’t stopped, as he continues to run LifeMine, which is exploring fungal genomes for new drugs, and also thinking up new company ideas. He remains as focused as ever on removing “undruggable” from the industry’s vocabulary.

“God didn’t make it undruggable,” he said. “It’s going to be biology, unmet medical need, that decides what actually gets drugged, and not people’s notions.”