Failure, faith and $8 billion: How Lilly's amyloid conviction brought it to the brink of Alzheimer's approval

(This story was originally published in February 2024, and is being re-run following the approval of donanemab.)

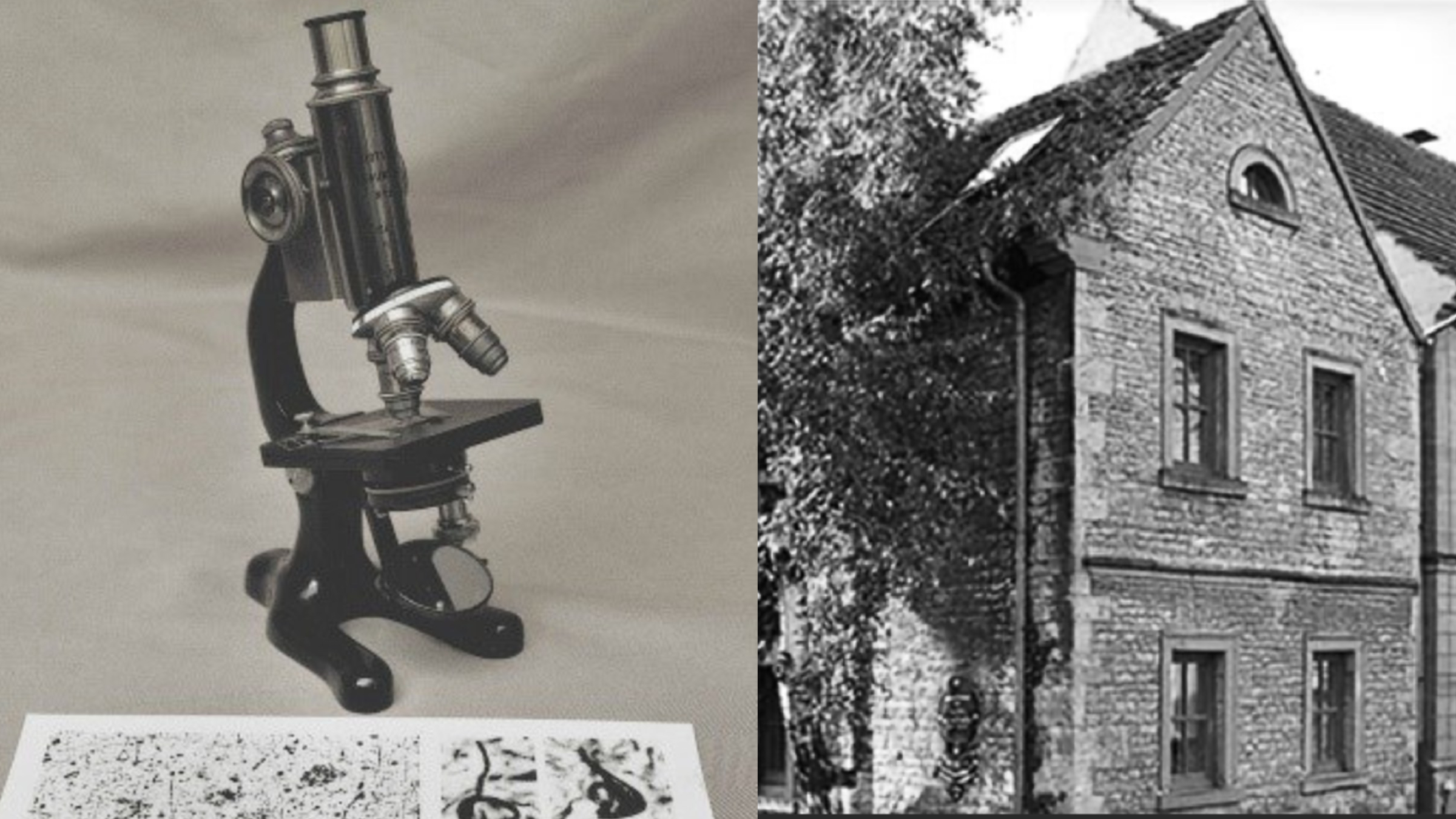

Twenty-nine years ago, Eli Lilly bought an old, ivy-covered brick house in Marktbreit, Germany.

The house was the childhood home of Alois Alzheimer, who had peered through his microscope and discovered suspicious looking plaques in samples of brains ravaged by dementia. Nearly a century later, in 1995, Lilly’s executives had high hopes for an experimental therapy that boosted brain receptors involved in learning and memory, and its scientists were hard at work on other pills that would stop Alzheimer’s disease in its tracks.

Lilly converted the house into a museum and conference center, and its scientists who visited could look into the famed German researcher’s antique microscope and imagine giving name to one of medicine’s most vexing problems. Lilly planned to host celebrations there when each of its new Alzheimer’s drugs got approved.

Those parties never happened. But nearly three decades later, the company is on the brink of receiving an FDA approval of its drug donanemab, in what would be the second amyloid-busting medicine granted full approval by US regulators — and what appears to be the most powerful.

Donanemab’s origins date back almost 20 years, surrounded by failure upon failure of other experimental treatments, with stories that are well-known. What’s far less appreciated is how, over the years, Lilly put crucial building blocks in place that would lead to success, and how the drug repeatedly escaped cancellation even as industry leaders grew increasingly disillusioned with the theory of the disease launched by Alzheimer in a prior century.

Steve Paul

Steve PaulEndpoints News spoke with a dozen current and former Lilly scientists and executives — many long retired — and academic researchers to understand the company’s faith in the amyloid hypothesis in the face of repeated failures.

“Lilly learned by trial and painful error how this amyloid hypothesis might play out,” said Steve Paul, a former R&D leader at Lilly. “And there were times where a reasonable person might have just said, ‘Hey, something’s wrong with the theory. It’s not right. It’s not working. We can’t win here.’”

The scientist

Ronald DeMattos arrived at David Holtzman’s lab at Washington University in St. Louis through a circuitous route. He’d worked at Parke-Davis, the Pfizer subsidiary behind what would become Lipitor, then was steered away from med school and toward a PhD. He thought he’d work on arterial disease at Stony Brook University. But once there, he was instead pushed to work on Alzheimer’s and became fascinated by the disease’s mysteries.

“The level of unknowns, that was the striking thing about the field back then,” DeMattos said. “I was a mutt of a scientist. I learned every technique you can imagine to do all the science myself.”

At Washington University, he’d caught Holtzman’s eye at a crucial moment for the field. Scientists at Elan Pharmaceuticals had immunized young mice with injections of a synthetic amyloid, and as they aged, the vaccine prevented the accumulation of amyloid plaques, appearing to stall the disease. For researchers like DeMattos and Holtzman, it got them thinking of other ways to target amyloid.

David Holtzman

David HoltzmanHoltzman’s lab was working with experimental antibodies that had been supplied by Eli Lilly that were meant to detect and measure amyloid. When DeMattos injected Lilly’s antibodies into mice to discover other proteins that amyloid interacted with in the blood, amyloid levels unexpectedly spiked. The chance observation fueled a theory that the antibodies could suck amyloid plaques out of the brain by shifting the balance of the free-floating protein in the blood.

“That’s what we began to test immediately,” Holtzman said.

According to one former Lilly scientist, the experiments might have broken the lab’s agreement with Lilly, but the results were too interesting for the drugmaker to ignore. The antibody would be renamed solanezumab and become the drugmaker’s biggest attempt to take aim at amyloid directly.

By 2002, DeMattos was working for Lilly, and the company poured resources into the approach as he spent the next decade-plus involved with the drug. When solanezumab failed at both removing plaques and slowing the disease in a pivotal trial in 2016, DeMattos called it “one of the toughest” moments of his life.

It was an equally challenging moment at Lilly. After the failure, the company’s CEO and chairman John Lechleiter summoned Jan Lundberg, the head of Lilly Research Labs, to his office at the company’s headquarters. (Lechleiter, through an intermediary, declined to be interviewed for this article.) The company’s insulin and diabetes drug sales had recently missed expectations, its stock was hovering under $70 a share, and there were rumors that Lilly could be gobbled up by a rival.

“I was prepared to fight,” Lundberg said of the moment. “Alzheimer’s disease is one of the last great frontiers in medicine that needs to be conquered. And the market opportunity for the company that succeeds with the first disease modifier is enormous.”

Lilly’s headquarters in Indianapolis had a view downtown that included Lucas Oil Stadium, the $720 million home of the Indianapolis Colts. When Lundberg walked in the room, Lechleiter pointed out the window.

“Do you know that we have just wasted shareholders’ money to the equivalent of what building a local football stadium costs?” he told Lundberg. “Should we really repeat that?”

Lechleiter’s question was, in a way, already being answered. While it attracted little notice at the time, DeMattos had already been at work for years on solanezumab’s successor.

Former Eli Lilly CEO John Lechleiter in March 2008 (Tom Strickland/AP Images)

Click on the image to see the full-sized version

The antibody

As Lilly advanced solanezumab toward what would be its eventual failure, the company’s Alzheimer’s labs were in a fierce rivalry with Elan Pharmaceuticals that would spark a crucial idea. While Lilly hoped that solanezumab would pull amyloid out of the brain, Elan and its partner Johnson & Johnson had an antibody, bapineuzumab, that went after plaques in the brain itself, binding to the deposits and spurring immune cells to gobble them up.

The approach was riddled with questions from the start about whether enough of the drug could reach the brain, or if the immune response would be problematic. But with its competitor already far ahead, DeMattos was tasked with making Lilly’s own plaque-busting antibody, an effort he began in earnest around 2005.

One of his first problems was figuring out how to target plaques and plaques alone — something Elan’s drug didn’t quite do. DeMattos thought if the antibody stuck to free-floating amyloid in the blood, it had little chance of making it into the brain. But a quirk of brain biochemistry, observed by others, would provide a starting point.

As plaques build up in the brain, protein-chomping enzymes sometimes snip off the first two amino acid building blocks of amyloid peptides. “It’s sitting there for so long, and your body is always reacting to it to a certain extent,” DeMattos said. “It basically exposes a new amino acid on the end that can form this little cyclic structure.” That target, dubbed N3pG, provided the foothold DeMattos needed. Now he just had to find an antibody that could do it.

While Lilly had dabbled with antibodies, in the late 1990s the drugs were largely the province of biotech upstarts. So in 2004, it acquired Applied Molecular Evolution, a small outfit with technology that allowed scientists to toggle individual building blocks in and out of antibodies, an especially useful trick for fine-tuning promising ones to improve their properties as drugs. It was also one of the last biotechs of its kind that hadn’t been snatched up by other pharma giants.

A young scientist there named Ying Tang was especially eager to show Lilly what the small antibody engineering company could do. Applied Molecular Evolution had almost run out of money around the turn of the century, and that near-death experience gave it the “motivation to work on anything,” Tang said.

Lilly had already asked a couple other antibody companies for help designing DeMattos’ plaque-targeting antibody and had been unsatisfied. And an early try by Tang was too weak to even move into a mouse study.

He tried to find someone who could take on the effort, but Alzheimer’s was just one small part of Lilly’s growing antibody efforts.

“We had so many projects from Lilly, we ran out of people,” Tang said. “So I said, ‘OK, I will take that as my side project, and work in the evening and weekend to get that engineering done.”

Those nights-and-weekends changes to the antibody would get Tang’s name on the patent, along with DeMattos and Lilly antibody scientist Jirong Lu.

The new molecule was later called donanemab.

The mice

Lilly’s leaders describe each of its attempts to treat Alzheimer’s as logical steps, where one failure informs the next effort. While there’s some truth to that, most of its drug programs overlapped because it was unclear whether preventing the formation of free-floating amyloid, removing existing amyloid, or breaking up the plaques would work best.

Jirong Lu

Jirong Lu“There was a lot of skepticism, even at the company,” Lu said. “We liked to say the amyloid cascade hypothesis is valid, but it really hadn’t been proven at that time.”

There was even early research in mice suggesting that amyloid-targeting antibodies seemed to help regardless of whether or not they cleaned up plaques, Holtzman said.

The discrepancies between mice and men started to become apparent in the 2000s. Elan’s vaccination study, in particular, created numerous headaches for DeMattos. The clinical trial was quickly halted in 2002 after several patients developed severe brain inflammation. For several years, papers and case studies tracking patient progress triggered vacillating hopes and doubts about the prospects for removing amyloid to treat Alzheimer’s.

“It was a very chaotic time,” DeMattos said. “And I remember many times having to go speak to management and say very clearly, this is why we’re unwavering, this is why we believe. These other data points, we obviously pay attention to them, and we interpret them. But none of them told us that the target itself was fraught.”

To keep pushing the effort, however, DeMattos needed more proof. There’s a truism in drug development that researchers have cured disease after disease in mice, only to see the drugs fail in humans. And DeMattos realized there was a problem with Lilly’s mice.

The rodents had been engineered in the 1990s to overproduce a mutant human amyloid protein in their brains. But over time, the genetic makeup of the colony had begun to drift, with the degree and timing of plaque buildup varying from mouse to mouse.

Thus began a four-year effort to selectively breed mice that had plaques at levels like those of people with the disease.

Most Alzheimer’s researchers testing antibody therapies were using the drugs to prevent plaque formation in mice that hadn’t yet developed them. “But we realized, in the clinic, that’s not what we’re going to be doing,” DeMattos said. He wanted to make sure that donanemab could remove amyloid plaques in an aging mouse, something that he thought other scientists hadn’t convincingly shown yet.

“Some people on the team thought we were nuts,” DeMattos said. “We knew we were going to need to have really robust data, because the competition was clearly ahead of us.”

When DeMattos injected the antibody into the mice, the plaque in their brains plummeted. Bapineuzumab, Elan and J&J’s competing antibody, had no effect — a result that foreshadowed the drug’s failure in clinical trials.

The clinic

When donanemab finally entered clinical trials in 2011, some of the first data almost killed the program. A Phase I study showed that most patients were developing an immune reaction to the treatment that researchers feared would soak up donanemab before enough drug could get into the brain.

“There was a real concern that that was going to torpedo the whole project,” said Patrick May, a former Lilly neuroscientist.

But the previous year , Lilly had approached a scientist who had come of age around the same time as DeMattos. Dan Skovronsky had written his PhD thesis with the subtitle of “Towards a Test of the Amyloid Hypothesis,” and his startup Avid Radiopharmaceuticals hoped to solve a very significant problem: To properly diagnose Alzheimer’s, the patient needed to be dead.

Avid had a radioactive molecule that clung to amyloid and made plaques light up on PET scans, meaning patients’ disease could be confirmed with a test instead of a sample of brain tissue, and Lilly wanted to buy the company. But in the middle of the talks, Lilly’s drug semagacestat — an Alzheimer’s pill designed to prevent the formation of amyloid protein in the first place — was terminated. Skovronsky was worried his life’s work would end up on the shelf.

“I didn’t want to become part of a company that was going to quit at the sign of failure,” Skovronsky said. He broached the subject with Lechleiter, Lilly’s CEO, asking if he was still interested in Avid, or whether they’d bow out of Alzheimer’s like so many other companies.

“John didn’t miss a beat. ‘We’re absolutely not quitting, we’re just getting started,’” Skovronsky recalled.

Dan Skovronsky (Credit: Eli Lilly)

Dan Skovronsky (Credit: Eli Lilly)Four months after the semagacestat failure, Lilly paid $300 million for Avid, and Skovronsky would quickly rise through the larger company’s ranks to become its top scientist.

And Avid’s tech soon proved its value to donanemab. As data from the Phase I study came in, Avid’s brain scans showed the drug wasn’t being hamstrung by the immune response — in fact, the results were stunning. Even a single infusion of donanemab reduced plaques in some patients, and kept them low at a checkup six or 12 months later.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” said Skovronsky. “That was such a compelling moment for us to realize that we really needed to put everything we had into making donanemab.

“If not for the PET scans,” Skovronsky added, “I think we would have terminated it.”

Skovronsky pushed to quickly put the company’s bets on donanemab. But three times now, Lilly had jumped from small Phase I studies into big and expensive Phase III efforts, only to see the drugs fail. “I felt like even if we got the energy to do that once more, the failure there would be unrecoverable,” Skovronsky said.

Skovronsky devised what he calls Lilly’s “Alzheimer’s 2.0 strategy,” part of which would be to run intermediate Phase II studies designed to get an early read on the drug’s effect. Key to those efforts were new ways to parse patients into finer disease stages based on levels of tau protein in their brain, believed to accumulate after amyloid.

CEO David Ricks was on board with the plan, and told Skovronsky that he trusted him on the science. When Skovronsky brought up the 2.0 strategy again a few months later, Ricks essentially told him to get back to work. “Right, get on with it,” Skovronsky recalls being told. “We don’t need to talk about it anymore. It’s a good strategy. Full speed ahead.”

On the brink of success, at last

Within days or weeks, Lilly is widely expected to win full FDA approval of donanemab. It has spent more than $8 billion researching and testing its Alzheimer’s drugs over more than three decades. While analysts once predicted that amyloid-lowering therapies could ultimately draw even greater sums in annual sales, it’s too soon to know if the investment will be worth it.

The clinical data, at least, appear to be strong. Lilly’s pivotal trial showed the drug slowed cognitive decline by 35% over 18 months, based on a scale developed by the company. It slowed the disease slightly less, by 29%, on the more widely-used scale, similar to the 27% slowing seen with Eisai and Biogen’s amyloid antibody Leqembi, which was approved last year.

Both drugs can cause dangerous and sometimes lethal brain bleeding and swelling, which seems to occur more frequently with donanemab, something that DeMattos’ mice experiments didn’t predict. Whether the modest benefits are worth the risk is up for debate.

“They both remove amyloid well, and you’re starting to see some subtle effects,” Holtzman said. “But they’re really relatively small. And that’s because it’s way too late to be targeting amyloid beta to have a massive effect.”

In retrospect, many scientists say it’s no surprise that many Alzheimer’s drugs haven’t worked, since they were attempting to treat patients already deep in the throes of the disease.

“It’s like trying to give a statin to reduce your cholesterol level in somebody who’s already got heart failure. That’s not gonna work. But if you give a statin to somebody who has high cholesterol, before they get a lot of plaque in their coronary arteries, that’ll help,” said Paul, the former Lilly R&D leader. “It’s not such a leap of faith to say, OK, how about if you do it really early?”

Those tests, which will take years to run, are already well underway. But last fall, Lilly and Eisai presented new analyses from previous trials of their drugs suggesting they were more effective, slowing the disease as much as 50%, in patients with lower amounts of tau in their brains, indicative of an earlier stage of Alzheimer’s. Lilly’s approval, decades in the making, years from now may look like just a first step.

There’s a fine line between conviction and delusion. For years, it wasn’t clear which side the amyloid believers would end up on.

“We’ve never lost sight that the amyloid was important. And I think that’s where lots of other groups kind of oscillated,” DeMattos said. “We never wavered.”

With each passing failure, their ideas inched closer to absurdity — until suddenly they didn’t.