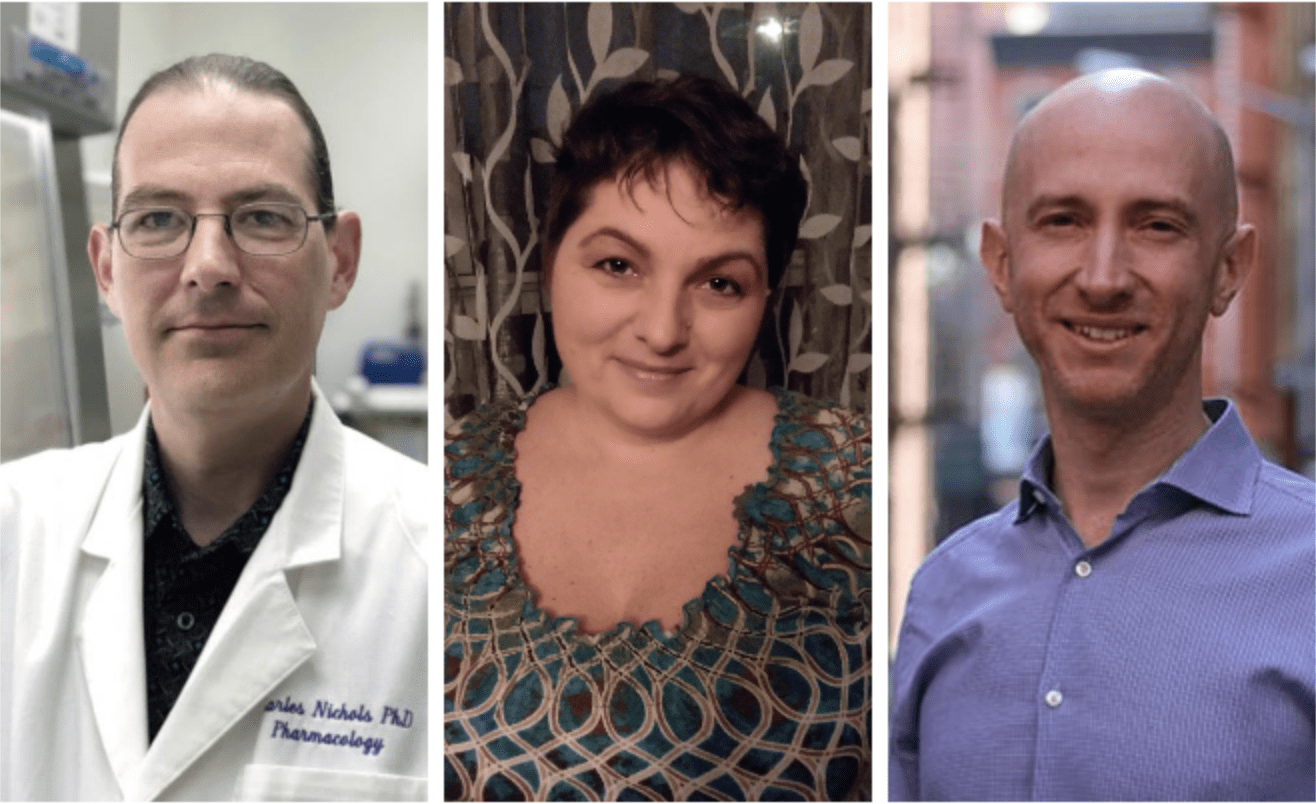

From left to right: Charles Nichols, Meghan Hibicke and Shlomi Raz

How do depressed rats respond to psychedelics? New data offer insight into the human experience

Despite tricky regulations, research evaluating the antidepressant potential of psychedelics in humans is mushrooming — and the FDA has already approved a nasal spray concoction of …

Sign up to read this article for free.

Get free access to a limited number of articles, plus choose newsletters to get straight to your inbox.