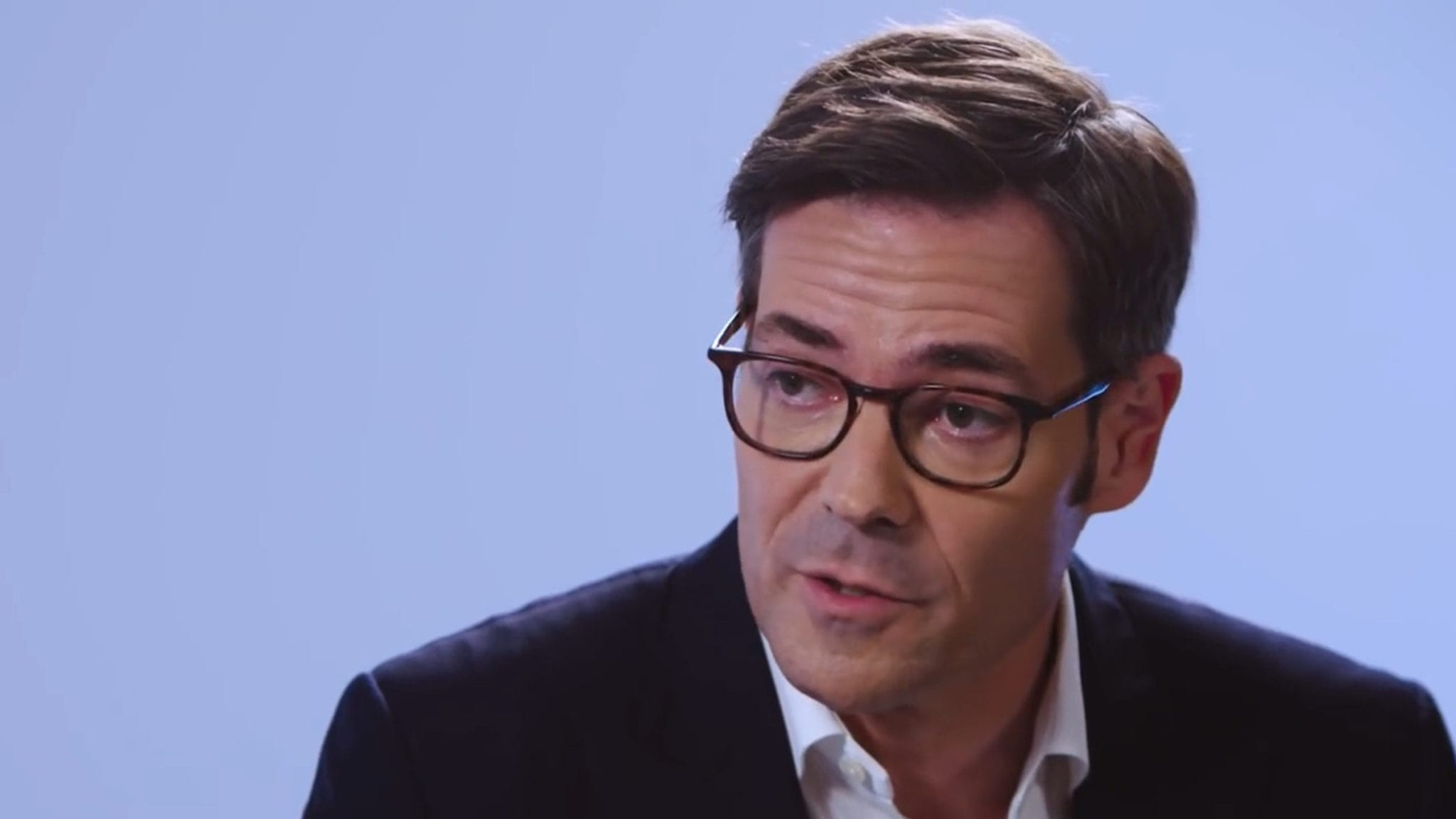

Mark Pruzanski, Intercept CEO (GlobeNewswire via YouTube)

Longtime Intercept CEO Mark Pruzanski departs as ailing NASH company tries to find its future

Mark Pruzanski, the CEO who turned “NASH” into a household name around biotech, guided his company to the precipice of a nascent field and then …

Sign up to read this article for free.

Get free access to a limited number of articles, plus choose newsletters to get straight to your inbox.