Pfizer’s paradox: Albert Bourla walks a fine line as he tries to turn around 2023's worst-performing big drugmaker

What happened to Pfizer?

In 2022, the company made Big Pharma history: breaking $100 billion in revenue, thanks to its Covid-19 blockbusters. CEO Albert Bourla became the public face of the drug industry’s pandemic heroism, as he touted plans to bring the “lightspeed principles” from Covid to other diseases.

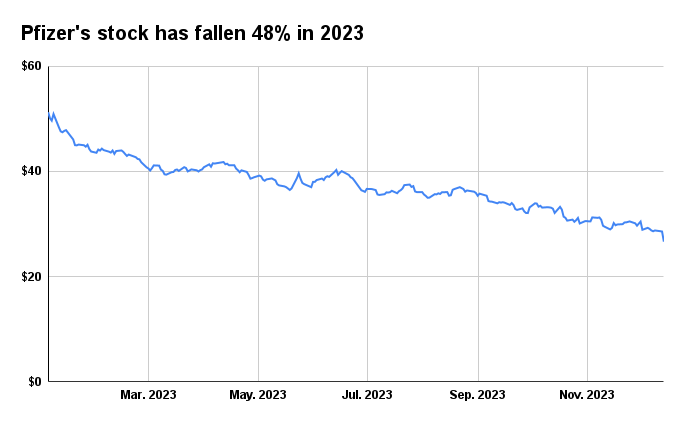

A year later, the pandemic shine is gone. Pfizer is the worst-performing large pharma stock $PFE of 2023, falling nearly 50% and erasing nearly $140 billion in market value. It has mismanaged Covid expectations, spent its pandemic windfall on deals that are eating into its earnings but may not pay off for years, suffered a failure for a much-anticipated obesity drug, and divested — on the relative cheap — an asset that Roivant months later turned into one of the best M&A flips of all time.

“2023 was a year of struggle, missed forecasting, and frustration for investors,” Evan Seigerman, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets, told Endpoints News. “The core tension is people feel they have squandered their Covid fortune and are now in a situation that’s really hard to get out.”

On Wednesday, Bourla tried to hit the reset button and get any remaining ugly stuff out of the way. The company announced another $500 million in cost cuts, and gave its next-year financial projections — issued earlier than in the past — that were lower than what the street was expecting. The stock on Wednesday afternoon was down 7%, headed for what would be one of its worst one-day losses of all time. And the last question on the hourlong call may have been the most revealing about how Pfizer is perceived, just a year after being atop the industry:

“Why wouldn’t a dividend cut be on the table?” Jefferies analyst Akash Tewari asked the $149 billion giant.

David Denton

David DentonCFO David Denton was emphatic that a cut wouldn’t happen — “Let me be clear, a dividend cut is not on the table,” he said — but it’s rare that corporate stalwarts like Pfizer even get asked. When General Motors and General Electric fell on hard times and cut their dividends in decades prior, the stocks of both fell into deep collapse.

“There is a path, but it’s not going to be easy,” Les Funtleyder, a healthcare portfolio manager at E Squared Capital Management, which is not invested in Pfizer, told Endpoints News. “Many healthcare investors are saying, ‘I’m going to find greener pastures.’”

Pfizer declined to comment beyond Wednesday’s call, or to make an executive available for an interview.

“As we close out 2023 and look ahead to 2024, we are very focused on addressing uncertainty and providing clarity,” Bourla said on the call, adding Pfizer’s business is robust and “capable of driving strong revenue and an attractive pipeline.”

Challenges beyond Covid-19 uncertainty

The problem starts, but doesn’t end, with its Covid-19 business, which in comparison to anything other than 2022 would be one of the biggest blockbuster franchises in the industry.

After bringing in $57 billion last year, Pfizer in October had to chop down its revenue expectations for its vaccine and antiviral pill, from $21.5 billion to $12.5 billion for 2023. And on Wednesday, it issued a forecast for 2024 of $8 billion, suggesting a further decline of 36%, well below Wall Street’s expectations. Bourla described the 2024 Covid-19 forecast as “conservative” and “something that we can easily make.”

But that decline is happening as multiple major drugs lose exclusivity. Five blockbusters — Eliquis, Ibrance, Xtandi, Xeljanz, and Inlyta — are expected to see key US patent expiries before the end of the decade. Those five drugs accounted for more than $15 billion in 2022 revenue.

Bourla has turned to dealmaking to fill that gap. Most notably, Pfizer will close its $43 billion buyout of Seagen on Thursday. But the pharma still has to show that the checks it has written will pay off, after paying $6.7 billion for Arena Pharmaceuticals, $5.4 billion for Global Blood Therapeutics, and $11.6 billion for Biohaven.

“People are realizing they buy all these things and they kind of fade away,” Seigerman said.

He called out Arena as an example, where there was tons of excitement when the deal was announced in 2021. But now, “no one is talking about” it, he said, despite a key drug, Velsipity, recently winning approval.

On the other hand, Seagen has grown revenues, delivered late-stage trial successes, and seen pharma interest surge in antibody-drug conjugates over the past few months.

Tension between dealmaking and debt, investment and cutbacks

This week’s C-suite shakeup reflects a new urgency to execute. Chief commercial officer Angela Hwang is out. Her departure, after nearly 27 years at the company, suggests the commercial performance wasn’t where the board wanted it to be, Seigerman said.

Aamir Malik

Aamir MalikBourla said he personally decided on the three commercial leaders going forward: Chris Boshoff, chief oncology officer; Aamir Malik, chief US commercial officer; and Alexandre de Germay, chief international commercial officer. Bourla said he’s known those three leaders for years, and trusts them with the job.

But the road ahead isn’t much easier.

Pfizer still needs to do deals to bring in $5 billion in yearly revenues by 2030 through dealmaking. But the company also needs to pay down its debt and protect its dividend — paying off the debt from Seagen will take 40 cents off next year’s earnings per share, Pfizer said.

And the company will have to do so while cutting costs in some areas, and aggressively investing in Seagen’s cancer business and pipeline.

“We have a great reason to be optimistic about the positive momentum in our business, the opportunity that the Seagen acquisition brings forward and Pfizer’s strong long-term growth potential,” Bourla said.