Accelerating Toward Human Relevant Nonclinical Test Methods

In November of 1937, editors from JAMA magazine penned a scathing letter about the United States’ inability to protect patients from toxins that masquerade as therapeutics, saying the drug development process was in dire need of laws with “common scientific decency.” In the preceding months, the nation had been riveted by the sudden deaths of nearly 100 people after taking elixir sulfanilamide. According to a congressional report, the elixir had been given to patients despite having only been “tested for its flavor but not its effect on human life.” Up until this point, drug manufacturers were not required to test therapeutics before sending them to market.

Under pressure, congress passed the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FDCA) which mandated that drug developers demonstrate the safety of new drugs through animal testing. Animals have since been the last line of defense, tasked with sussing out which compounds a human can and cannot tolerate by showing first-hand the ill effects of toxic chemicals.

The bill that called for animal testing is not surprising. At the time, the only way for researchers to truly investigate a new drug’s pharmacotoxicology was to either take the drug themselves or else give it to animals as proxies. However, in the nearly 80 years since the elixir sulfanilamide disaster, science has advanced and with it, a growing skepticism of animal models has developed.

All of the news, delivered with full-text to your inbox. For professionals discovering, developing, and marketing biopharmaceutical drugs.

Though animal models have played a pivotal role in the evolution of modern pharmaceutical development, they’re no longer a gold standard. Too often, they classify toxic drugs as safe, only to be revealed as dangerous through the agony of patients. Advanced model systems have been developed that more accurately emulate human tissue and appear to be highly sensitive indicators of drug toxicity—all without the ethical and financial burdens that come with animal testing.

It’s against this backdrop that the FDA Modernization Act was developed, an amendment to the FDCA that eliminates the mandate for preclinical animal testing. If enacted, it would be the latest in a global movement to improve patient and consumer safety by divesting from animal testing.

A Global Movement

The use of animal models in research is prolific and for good reason. It is exceedingly difficult and important to study how chemicals behave in complex, multiorgan systems. The transit of a compound from one organ to another may change it, affecting its pharmacological properties and potentially rendering it toxic. Animals, and particularly mammals, possess the same organs that humans do and can thus be a close approximation of the human body.

However, animal-models are far from perfect and come with a host of ethical concerns. Even with multiple layers of regulation in place, stories abound of animal abuse and suffering. With no suitable alternative, researchers have persisted with the mantra that we should refine, reduce, and replace experimentation on animals wherever possible.

To that end, new model systems have been developed that closely resemble human tissues and may help to reduce and replace animals in preclinical screening. For example, synthetic human skin—formed from donated tissue—has been validated as a strong preclinical model for assessing skin irritation and damage caused by cosmetics, negating the need for animal testing.

In recognizing the value of these non-animal models, 41 countries have banned the sale of cosmetics that were developed using animal testing. Multiple US states have enacted similar state-level bans, and, just this year, The Humane Cosmetics Act was introduced for congressional consideration. If enacted, this bill could significantly reduce the global use of animals in cosmetic testing.

Curtailing animal usage in environmental and therapeutic toxicology has been slower, but progress has been made. The EPA recently announced plans to severely reduce animal usage when screening new chemicals, and the NIH has signaled intent to substantially decrease the use of primates in its research.

These are the rumblings of change that foreshadow a future without animal testing. But, to realize that potential, we’ll need to continue to invest in the development of advanced model systems like organ-on-a-chip (organ-chips) technology and legislation such as the FDA Modernization Act.

Organ-Chips and The FDA Modernization Act

Among its stipulations, the FDA Modernization Act would allow researchers to use the most accurate model systems when assessing a new compound’s safety, eliminating the requirement that all drugs be tested in animals before clinical trials.

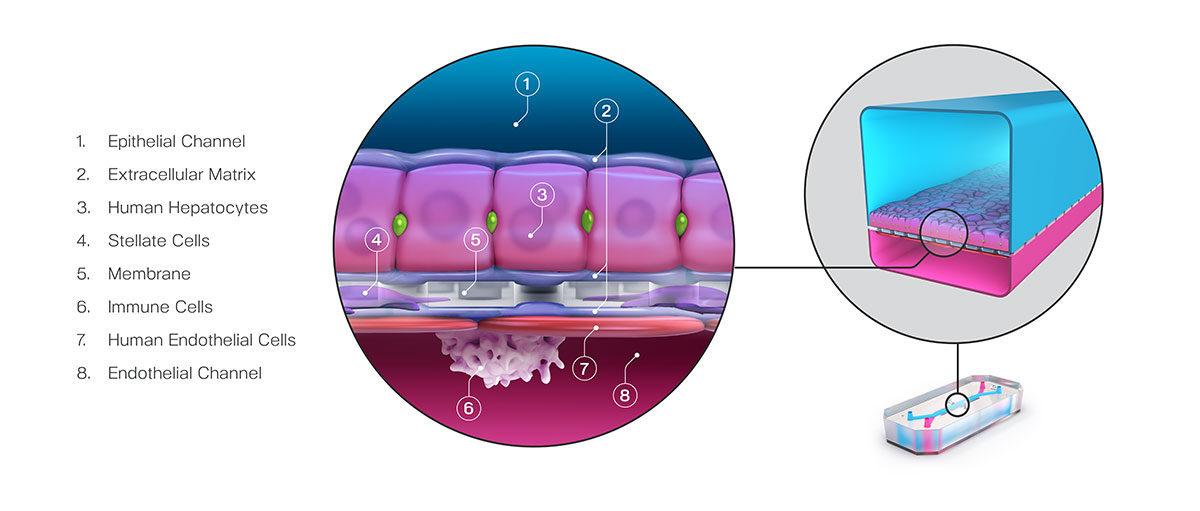

Fuel for this bill has come from a growing body of evidence showing that organ-chips can produce highly sensitive and accurate models for testing drug toxicity. Generally, organ-chips are in vitro systems that combine biomechanical forces and heterogeneous human cell populations in a 3D tissue architecture to mimic specific tissue units.

In a recent study, researchers from Emulate described a large study in which 780 Liver-Chips were tested for their ability to identify toxic compounds. Notably, each toxin used in this study had been classified as safe in animal studies, only showing toxicity once given to patients. Unlike animal models, these organ-chips correctly identified the compounds’ toxicity with a sensitivity of 87%.

These promising results suggest that organ-chips may one day replace animal models. Much more research is needed before that day comes. But, for now, organ-chips can be effectively used to ensure that animals are not wasted on drugs that are destined to fail. Researchers can integrate organ-chips prior to animal testing as a filter against toxic compounds, ensuring that animals are only used to test the most promising candidates. The FDA Modernization Act encourages this integration and paves the way for models like organ-chips to potentially replace animals altogether.

A Law with Common Scientific Decency

The tides of change are in full swing. We see a trend of global divestment from the use of animals in cosmetics testing, and a growing movement to reduce and replace animals in therapeutic and chemical screening. By embracing modern technology and ever more accurate in vitro model systems, the FDA Modernization Act is a law that brings us another step closer to common scientific decency and a more humane future.