Alzheimer’s: Learning From a Legacy of Bitter Setbacks

by SHEHLA SHAKOOR, JOHN CARROLL, ARSALAN ARIF, and the ENDPOINTS NEWS TEAM

In biopharma R&D, the biggest and best drug targets always involve unmet medical need—and Alzheimer’s fits that definition better than any other major disease.

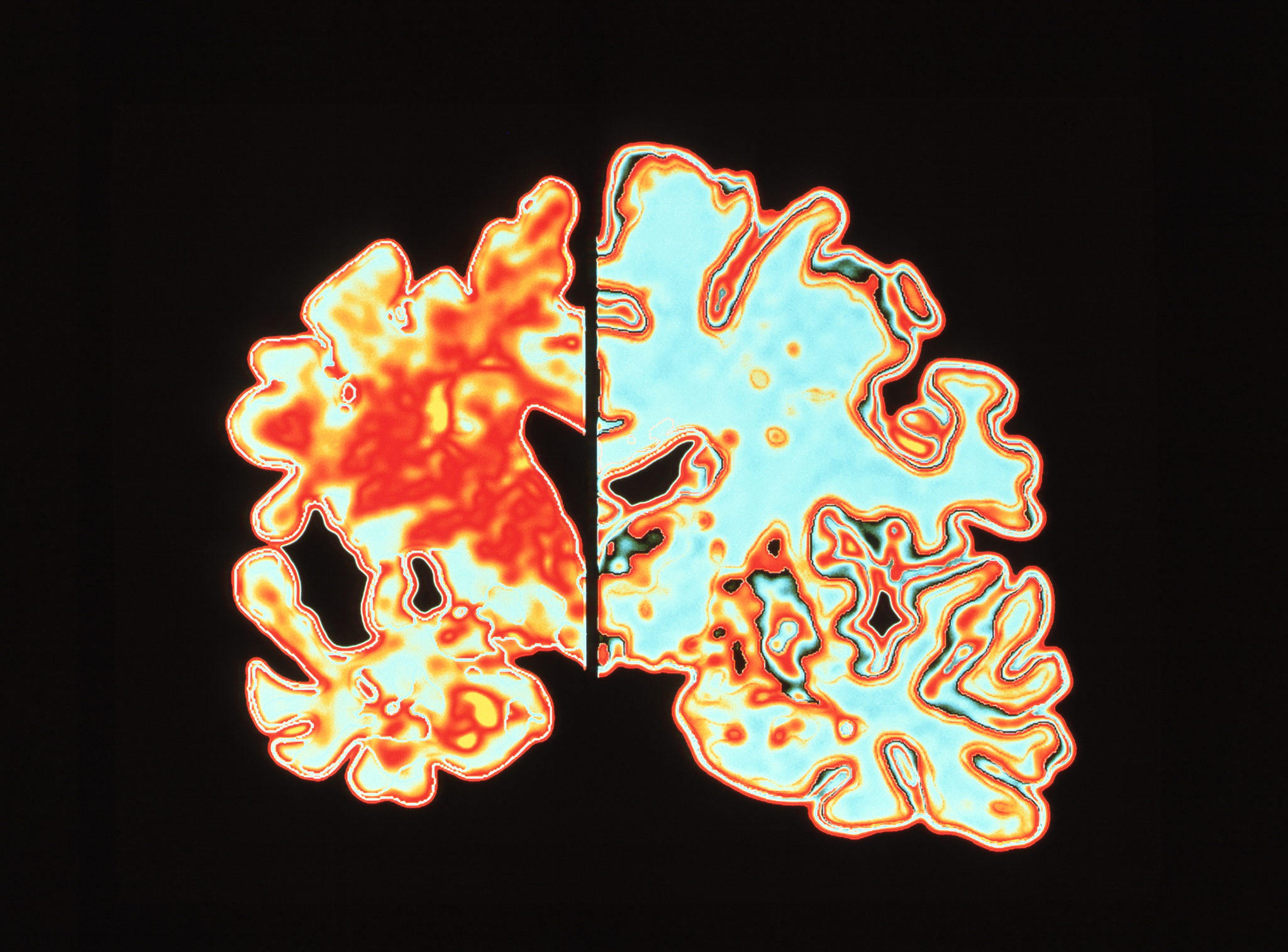

There’s good reason for that, and it’s inside our heads. The circuitry of the human brain is incredibly complex, with some 100 trillion synapses ferrying electrical messages between neurons in a constant frenzy. In the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, those biologic processes break down. Messages go awry, often to catastrophic results.Investigators have been focusing on toxic concentrations of amyloid beta that clog up those synapses and on a substance called tau that’s found inside neurons. While some big players like GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca have stepped back in recent years, preferring to focus their resources in diseases where they’re likely to make a bigger impact, and more quickly, a group of big and small drug developers remain stubbornly committed to the field.

To understand why they’ve doubled down, you need to understand the numbers. And they all point to a crushing cost from a deadly serious aging disease.

Of the 5.5 million Americans with Alzheimer’s, 4% are under 65, according to a new report from the Alzheimer’s Association. That number swells to 16% among seniors between 65 and 74, then 44% for the next decade and 38% in the 85-and-older group. That’s a lot of people, and in an aging population, the numbers are about to grow.

It’s not just patients, either. There are close to three unpaid caregivers for each of the Americans with Alzheimer’s, and they’re devoting increasing amounts of time to their afflicted family members.

The cost of Alzheimer’s care will hit $259 billion this year. And that pales in comparison to what’s coming.

By 2050, the cost of care is expected to quadruple, to more than a trillion dollars. Medicare can’t handle that kind of math. Nor can the healthcare systems in other countries that will have to adjust to even bigger patient pools as population demographics go increasingly gray.

Numbers like that are scary for society, but they spell a big opportunity for drugmakers. If anyone creates a treatment that modifies the progression of the disease—or even delivers gains on the symptomatic side—that’s a golden ticket. The potential payoff could drive billions in annual profit.

As a result, companies like Eli Lilly, Roche and Merck & Co. have been pumping billions of dollars into late-stage research projects. The payoff over the past 14 years: $0.

As a result, companies like Eli Lilly, Roche and Merck & Co. have been pumping billions of dollars into late-stage research projects.

The payoff over the past 14 years: $0

Pharma companies have announced one failed study after another. The growing litany includes every single Phase III readout. Alzheimer’s R&D hasn’t even produced new additions to the short list of modestly effective symptom-focused drugs on the market.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that each failure has offered at least marginal insight into what went wrong before. Deepening experience and improvements in technology illuminate which paths researchers should continue to follow, and where new paths should be blazed.

Large concentrations of non-Alzheimer’s patients were accidentally scooped up into earlier studies; now, diagnosis is more precise and patient recruitment more discriminating. Trials are better run, thanks to the emergence of a global network of sites. They’re sharpening standards as investigators track the cognitive and functional abilities of trial participants.

Meanwhile, researchers’ thinking has evolved, pushing steadily upstream to earlier and earlier stages of the disease.

Old conflicts between disease triggers have begun to resolve into a better appreciation of the kind of drug cocktails necessary to change the current Alzheimer’s prognosis—dementia and death—to a manageable, chronic disease that no longer wipes out memories and personalities.

Still, experts in the field agree that something concrete needs to happen in drug development. Something that will actually benefit patients. And the sooner the better.

Sign up to read this article for free.

Get free access to a limited number of articles, plus choose newsletters to get straight to your inbox.