Biopharma leaders paving the way for LGBTQ+ scientists, patients, entrepreneurs and C-suites

To intro last year’s inaugural Endpoints News feature on LGBTQ+ leaders in biopharma, I wrote about the movement and progress being made for this community.

I feel I might have jinxed it in some ways. Anti-LGBTQ+ bills are running rampant through the US, children can no longer read gay books in some regions and this community still feels misunderstood by the pharma world.

Being LGBTQ+ is just one part of a person’s identity, but a critical one that often is not visible to outsiders, as some people on this year’s list point out. Others worry the recent onslaught of anti-gay rhetoric in some corners will force LGBTQ+ people to no longer feel comfortable speaking out or being open about who they are in the workplace.

“The rate at which the progress is accelerating is not as high,” says scientist-turned-investor Mira Chaurushiya. “Maybe that’s to some extent reflective of progress we’ve made as a community, but I think there’s still a ways to go.”

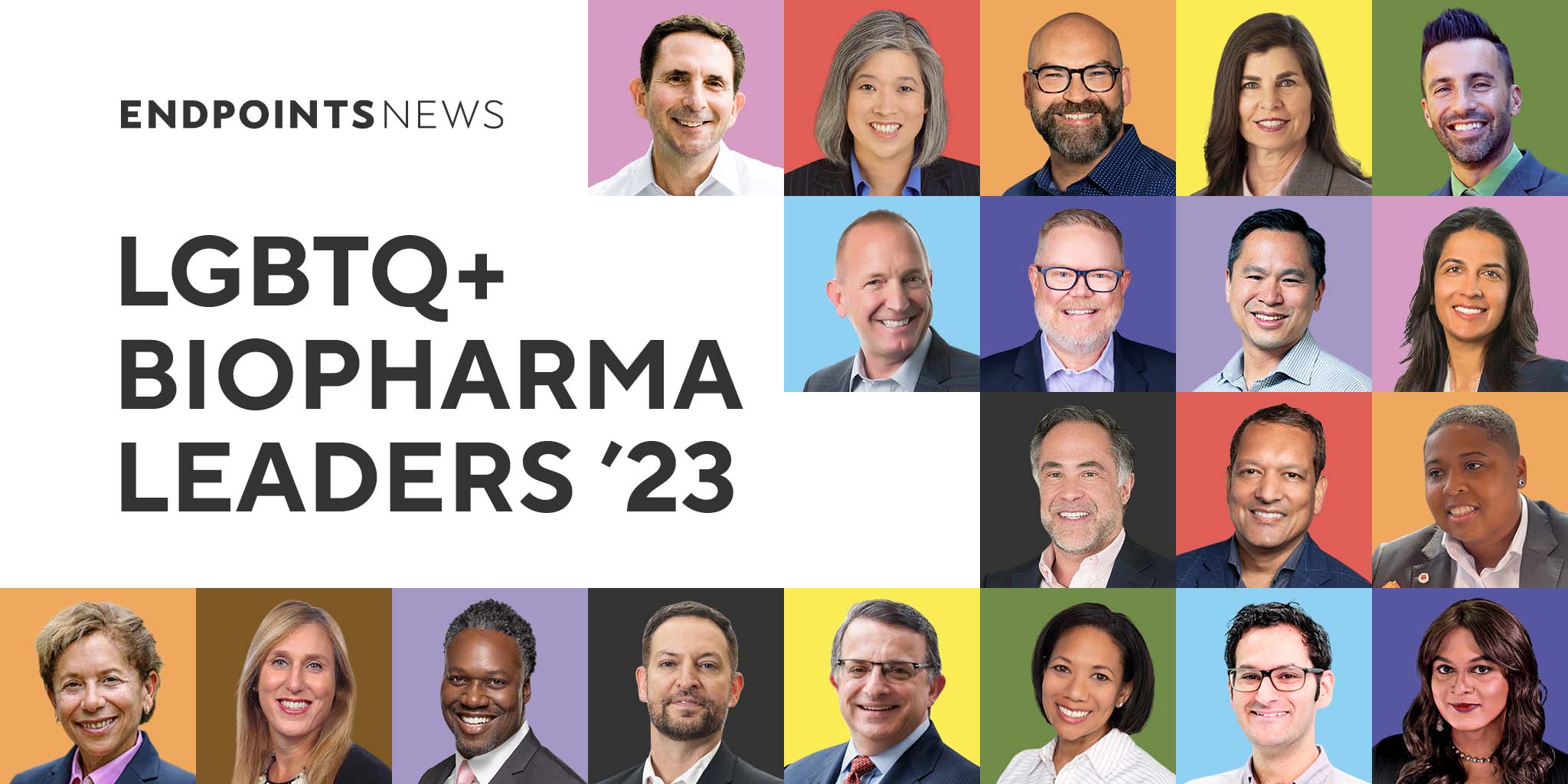

This year’s honorees do speak out, whether that’s in the halls of their biotechs, on visits to pharmaceutical sites outside the US, in boardroom discussions, on the manufacturing floor, in clinical research and in bringing a new drug to market.

As with lists like these, we weren’t able to highlight everyone who was nominated, but I hope we have been able to paint a broad look at who makes up the LGBTQ+ community in the biopharma industry.

If you’re reading this while at Endpoints’ first day of BIO panels at the Seaport Hotel, then be sure to tune in again for day 2, when I will virtually moderate a discussion with some of this year’s honorees about LGBTQ+ issues. — Kyle LaHucik

- Edith Perez — Bolt Biotherapeutics chief medical officer

- Eliav Barr — Merck CMO

- Tia Lyles-Williams — Goffman Bougard CEO and founder

- Alaina Kupec — Gilead senior director of portfolio strategy & analytics

- Joan Lau — Spirovant CEO

- Ramsey Johnson — OUTbio founder

- Susan Whitehead — PACT Pharma president and COO

- Paul Hastings — Nkarta CEO and BIO chair

- Celia Sandhya Daniels — Rebekon Consulting CEO and founder

- Martin Chavez — Recursion chair

- Jayson Johnson — Genentech diversity & inclusion

- Mira Chaurushiya — Westlake Village BioPartners managing director

- Greg Vladimer — Exscientia VP

- Peng Leong — BioAge chief business officer

- Joshua Cohen — Braeburn medical chief

- Amit Rakhit — Flare Therapeutics CEO

- Coy Stout — Brii Biosciences SVP

- Allene Diaz — Ionis and Mersana director

- Jon Newton — ICON VP

- John Davis — Sonoma Biotherapeutics interim CMO

- Name Edith Perez

- Company Bolt Biotherapeutics

- Position Chief medical officer

An oncology marathon: From microscope adventures to clinical research to biotech exec

At around mile 23 of 26.2 along the Atlantic Coast in Jacksonville, FL, Edith Perez had pushed her body to the limit, giving it her all in a marathon she helped co-found as a Mayo Clinic researcher and doctor of a patient who’d thrice been diagnosed with breast cancer and now leads the city. The paramedics came in and needed to devise a quick in-the-moment fix.

They settled on crab cakes. She rehydrated — she skips out on the energy gels that many marathoners stock up on for races — and finished the DONNA Foundation marathon, one of the more than half-dozen times she’s run that distance.

“That’s a classic Edith of just going at it until her body says no more, and then she figures out a way around that,” says Willie Quinn, her Bolt Biotherapeutics colleague.

A renowned Mayo Clinic oncology researcher, leader of an early 2000s Herceptin trial that helped change the landscape for early-stage treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer, and, more recently, biopharma executive, Perez is known to lay it all on the line, not only in marathons but in her everyday work as a researcher and drug developer.

Her work in science dates back to her days growing up in Puerto Rico when her teacher mother and businessman father gifted her a microscope. She’d go around town asking friends if she could prick their fingers so she could view their blood on a microscopic level. The original career dream looked more mathematician than clinician, but her grandmother’s sudden passing altered Perez’s vision for the future — “I thought, oh my gosh, if I had been a doctor, perhaps I could have saved her,” Perez recalled thinking.

“I want to do something for the future, gosh, but I want to have an impact today,” Perez said.

Science ruled every aspect of her professional life at the beginning of her career in clinical research and drug development. Little room could be eked out for much else.

“At the beginning, it never crossed my mind, actually. I thought you could do your work, you bring your intelligence and your soul and you will get equal opportunities,” she said. “That was very naive. And then, over the years, I realized that’s not the case. We all need to speak up. Some of us have to speak louder than others to be heard.”

But over the years, she became more accustomed to bringing up her non-work life while in the office, lab and board rooms, which entailed talking about her wife and taking part in Pride Parade floats during her time as an oncology leader at Genentech. She’s also become heavily involved in making studies of new cancer therapeutics more representative of the patient population. The mission elevated her to the top of Stand Up to Cancer’s efforts in the field a few years ago and contributions to a similar committee within the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine that reported their findings last fall.

“When you’re new to cancer research, and you talk to really brilliant Nobel laureate scientists, sometimes it’s really hard to understand,” says Russell Chew, a pilot-turned-airline-executive who’s now CEO of Stand Up to Cancer, a nonprofit that’s helped fund research of multiple approved cancer treatments. “If you speak to Edith, she speaks like a normal person, right, and yet she’s this wealth of knowledge, and I think that warmth and that approachability, I call it approachability, but that ability to communicate at the level of whoever you’re talking to is actually really an important skill.”

Perez sees it as part of her mission to meet people where they are and bring them together.

“I’ve been paying more attention to this in traditionally underserved groups in terms of open discussions about all of us being part of one human race,” Perez explains. “That’s why I decided that it’s part of my life’s journey [that] I need to think about all of these components as part of the work that I do every day more than just thinking about the science or more than just thinking about drug development.” — Kyle LaHucik

- Name Eliav Barr

- Company Merck

- Position Chief medical officer

Medical leader’s push for LGBTQ inclusion in Gardasil clinical trials set the tone for the rest of Merck’s pipeline

Whenever Eliav Barr visits a Merck site outside the US, the chief medical officer requires an LGBTQ+ gathering. As the company’s most prominent drug development leader, he sees queer acceptance and openness as part of his calling, something he’s reminded of when colleagues in Poland thanked him for actively talking about having a husband.

“I feel like, oh my God, I’ve become the poobah, but I always want to make sure they carve out a pride event during each of the visits so that we can raise visibility,” Barr told Endpoints News. Merck elevated him to CMO last year after nearly three decades of leading work on its HPV vaccine Gardasil, HIV medicines, hepatitis C vaccines and other therapeutics.

Barr’s physician father and nurse mother planted the seed for his medical career. He trained at Johns Hopkins during the “darkest days of the AIDS epidemic” in the late 1980s. “The death all around you and the homophobia and all that was really formative in my mind about the importance of being an out person in medicine,” he said.

He went on to the University of Michigan and then taught cardiology at the University of Chicago, where an affinity for the tangible translation of science to public health — by way of clinical trials — set him up for a career in pharma. The Windy City is also where he met his now-husband, Paul, in 1994 via a print ad in the Chicago Reader, a local alternative newspaper. (They’ve been together 29 years, as Paul chimed in mid-Zoom interview to remind him.)

Barr ascended to the CMO role after paving the way for Gardasil to get approved in 2007 and its follow-up, Gardasil 9, in 2014. The vaccine was meant to prevent a sexually transmitted infection that can hasten cervical, genital, anal, head and neck cancers. But when he joined the program, the trials were focused on heterosexual women.

Barr ensured lesbian participants could also join the studies, and “there was clearly a little bit of tension or nervousness” at the company at the time. Then, in what he calls his “first major contribution to increase LGBTQ visibility in the workplace,” Barr proposed a study of the vaccine in gay men.

“I had to use the icky term anal cancer — by the way, men and women both get it — and I remember the discomfort factor of the senior leaders when I brought up the study. But we did it, and it turned out to be really important because during that time we also were able to teach a lot of sites how to do screening for anal cancer,” Barr said. People living with HIV would also be included. That would also translate into Merck’s HIV pipeline, where he made sure transgender women were not left behind in clinical trials.

Those concerted efforts to ensure LGBTQ+ people were included in clinical trials became ingrained in the company’s clinical development apparatus, Barr said.

Barr’s influence is also spread across more than 3,000 global employees who are members of the drugmaker’s Rainbow Alliance, an LGBTQ+ group with three dozen company chapters. As executive sponsor, Barr’s budget partially goes toward funding events, sponsorships, Pride Month lectures and more. They also attend career fairs with LGBTQ+ networks. This year, more will be done for transgender people, he said, “because life is already tough for them, and this has been just a particularly evil past year, so making sure that they’re visible and part of the discussion.”

He’s working to expand the alliance’s presence in regions that aren’t as LGBTQ-friendly as where he is based, in Philadelphia.

“In countries that are much more difficult for LGBTQ people to feel comfortable in and even countries like Brazil,” Barr said, where there are cultural challenges: “It’s very macho and guys doing guy things, and gay people are always kind of marginalized there, but really pushing hard to institute visibility and sensitivity, not just in the US but internationally.”

When he’s not visiting international sites as part of his self-professed workaholic personality, Barr is pushing Merck’s “policy people in Washington to be supportive of legislation that HRC [Human Rights Campaign] and others put out there.” — Kyle LaHucik

- Name Tia Lyles-Williams

- Company Goffman Bougard

- Position Founder & CEO

‘Use biotech as a medium to rebuild’ communities of color

Tia Lyles-Williams is the first queer Black woman to own a drug manufacturing company. Lyles-Williams founded LucasPye Bio, a contract manufacturing operation in Philadelphia, in 2018. She has made equity and inclusion central to her mission and hopes her company can bring new jobs and economic opportunity to underserved communities of color.

In 2022, LucasPye Bio entered a deal with the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority to transform a six-acre vacant lot into a campus that will house its headquarters and life sciences accelerator HeLaPlex, which Lyles-Williams also co-founded. And at a biotech summit at the White House last year, Lyles-Williams spoke about biomanufacturing and advocated for more inclusivity and diversity at all levels — from patients to C-suite executives.

Endpoints talked to Lyles-Williams last month about her work and advocacy. This interview has been substantially edited for length and clarity.

Wu: I saw that you named LucasPye Bio after the maiden names of your two grandmothers. What made you decide to do that?

Lyles-Williams: The reason I named it after my two grandmothers is because — most people don’t know this — historically, all biopharma companies are named after the last name of white men. These are not made-up names. Pfizer is someone’s last name. Merck is someone’s last name. Abbott is someone’s last name. So I chose to name it after two African American women, as the first African American woman to own a biomanufacturing company, second to the first African American man, Dr. Percy Lavon Julian.

In honor of him and what he also did to diversify the industry, first to hire women and people of color as engineers and scientists at Julian Laboratories — there’s a lot that I owe him to where I’m at today — and then I wanted to honor my grandmothers by using their maiden names instead of a traditional male name because I have my last name, so I used their maiden names as the name of my company.

Wu: On the topic of diversity, when it comes to people who work in biotech, it’s very much a white, male-dominated space. How does that impact you and your day-to-day with what you’re doing here trying to build your company?

Lyles-Williams: Oftentimes, when we’re reaching out and working with the business development team to reach out to different pharma companies, we get looked at as if we’re some type of — no disrespect to small businesses — but like we’re some type of catering agency. So they oftentimes don’t put us in contact with the head of business development or the COO or the CEO. It takes a lot for us to get through to them and for them to take us seriously.

You don’t see people who look like me, whether it’s at the high level or at the low level. It’s been like that my whole career. So we are doing a workforce development program that we will be piloting officially this fall. We’re working in partnership with some name organizations here in the city of Philadelphia — the UC Science Center, Jefferson Institute for Bioprocessing, Philadelphia OIC, and then the Business Center for Entrepreneurship and Socialization. So we got some things in the works to help with that.

Wu: I’m curious how many times you’ve walked into the meeting room, and there has been someone who looks like you in that room as well.

Lyles-Williams: Maybe twice. Twice throughout my whole 22-year career.

Wu: So, what’s your vision moving forward for your company?

Lyles-Williams: Good question. Once the markets get a lot better, we want to work with startups. Outside of that, our vision is to expand LucasPye Bio to countries that don’t have the technology or knowledge or are a little bit less fortunate.

As a former employee of Baxter, but before my time there, I learned about Baxter building a manufacturing facility in South America — I forget which country — and the reason they did it is because South America was a huge market for their bread and butter, a hemophilia drug.

And that country couldn’t afford the medication but was the biggest market. So their solution was, “Let’s build a facility and license the drug to the facility,” and now people are working, they have the infrastructure to afford healthcare, and now they have the health insurance to be able to afford the drug. We want to mimic that same thing. But we want to put it in similar countries where their indigenous community will have access to a higher level of quality of healthcare and will be able to work high-quality jobs and further their careers in biotech.

I look at biotech the same way that the US and communities of color benefited from the steel mill. Back in the day, my grandfather worked in a steel mill in Gary, IN. He also worked in the steel mill in Pittsburgh. We want to do something similar where we use biotech as a medium to rebuild and positively influence the economy where there’s a community of predominantly people of color or indigenous people. — Lei Lei Wu

- Name: Alaina Kupec

- Company: Gilead

- Position: Senior director, portfolio strategy & analytics

Fighting to help others ‘be themselves authentically’

Alaina Kupec never intended to be in the spotlight. Her ideal life post-transition was one in which she wouldn’t have to talk about her gender history.

But when House Bill 2 barred people in her home state of North Carolina from using the bathrooms that aligned with their gender identity, she said she “couldn’t stand idly by.” Kupec spoke at an event shortly after the legislation became law in 2016, and “it just kind of snowballed from there.”

“We’re a small community, but then people willing to be visible in it is a very, very, very small number as well,” Kupec said. “Part of what’s driven me is just to help people understand what’s the difference between political rhetoric and the lived experience of somebody who’s transgender.”

After that first appearance, Kupec met with legislators and advocated for transgender rights in a 60-second ad spot that aired during both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions. She had been at Pfizer for more than a decade at the time, following a four-year stint in the Navy. Her roles at the company spanned district manager to, later, access lead for the atopic dermatitis drug Eucrisa.

North Carolina lawmakers repealed the bathroom law in 2017, but when former President Donald Trump announced a ban on transgender military service later that year, Kupec spoke out once again. Her wife calls her an “accidental activist.”

“It took me 40-something years of my life to finally be able to have the courage to live my life authentically,” Kupec said. “All that I want is for young people who know in their hearts and their brains who they are on the inside to have the opportunity to be themselves authentically.”

Kupec is now senior director, portfolio strategy and analytics at Gilead, where she leads work on virology and inflammation. She started at Gilead in 2018 amid a big move from New Jersey to San Francisco for her wife’s job at Google. At the time, Gilead was looking for an access lead on a commercial team for the JAK inhibitor filgotinib. After helping launch Pfizer’s Xeljanz, it was the “perfect opportunity at the perfect time,” she said. Gilead once touted filgotinib as a potential blockbuster but ended up handing back much of the rights to Galapagos following a rejection in rheumatoid arthritis.

While at Gilead, Kupec has done access work on the company’s Covid-19 antiviral remdesivir, also known as Veklury, and more recently worked with the closely-watched capsid inhibitor for HIV-1 lenacapavir, which scored an approval at the end of last year and is now marketed as Sunlenca.

Since joining, Kupec has been involved in employee resource groups, including veterans and LGBT groups. Earlier this year, she moderated the company’s Transgender Day of Visibility event. Transitioning mid-career, she added, can feel like walking a plank. You don’t know how you’ll be received by your peers, leaders and clients.

“I navigated the professional workplace my first half of my career as a white male with white male privilege, and now I navigate as a woman in the workplace. And so it gives me a unique perspective in the world,” Kupec said. “My hope is that maybe companies will see that we have hidden talents to tap into.”

Last year, Kupec and her wife endowed a collection of transgender-positive materials at her alma mater NC State University. The collection aims to combat misinformation and provide accurate information free of political bias.

Outside of work, her wife and three sons keep her motivated. They live on the water in Florida, which Kupec describes as her “zen place.” However, Florida lawmakers in early May passed a bill that restricts gender-affirming care for minors and could even potentially strip parental rights from parents who support their transgender children.

“On a personal level, SB254 is abhorrent,” Kupec said. “To take the decision on how parents and medical professionals can best treat their child/patient and put it into the hands of lawmakers is something our founding fathers would find deprives an individual of their liberty.” — Nicole DeFeudis

- Name Joan Lau

- Company Spirovant

- Position CEO

An introvert hosts Vegas-style biotech get-togethers in Philadelphia

Joan Lau embraces her introverted self – she jokes, “Big I, not shy.” The CEO of Spirovant, a gene therapy biotech, also uses her natural inclination to push outside of her comfort zone and remind herself not only to make connections but to facilitate them.

To that end, she sets up biotech get-togethers among her local Philadelphia community, hosts hiking groups for women and helped create an LGBTQ+ group for leaders on a Penn alumni board, of which she’s a member.

Lau began her career in drug development at Merck R&D and then moved into smaller biopharmas in Philadelphia. She co-founded Militia Hill Ventures in 2013, with cystic fibrosis-focused Spirovant being one of the companies that came out of it in 2016 and now wholly owned by Sumitomo.

She and her wife, a retired biopharma veteran, met at a University of Cincinnati College of Medicine potluck dinner when Lau was in grad school there, and they now have a teenage daughter, who recently stepped into the driver’s seat.

The former Human Rights Campaign board chair recently talked to Endpoints about the evolution of her career, her introverted social justice activism, her goal to be transparent and true, and the importance of connecting.

The following Q&A is edited for length and clarity.

Snyder Bulik: What kind of community activities or advocacy do you do?

Lau: I have a hiking group of just women, Asian women, in fact. We hike every Sunday at 7:30, and we come from all walks of life. And then, I organize dinners for the biotech community. We go out to eat – it’s Vegas style, it’s agenda-less. Sometimes we go to a restaurant, but we’ve done curling — you know, with the sliding rock and the brushes? — and we’ve done sporting clays.

Just lots of gathering events. I’m an extraordinary introvert, which doesn’t make sense, I know. But getting together is important and making sure everyone can be themselves.

Listen, I’m a queer Asian woman who doesn’t drink. I’m super short. There are so many things about me that don’t fit the typical — I often feel left out. So I’ve learned if you can just help people feel a little more included and feel like they can belong and should be there, it just makes a huge difference.

Snyder Bulik: What is the work that you do or your involvement at Penn?

Lau: The Penn alumni president heard from a student that there isn’t a lot of representation of LGBTQ people within the Penn alumni organization. So she took a look. And she was very surprised that that was indeed true. So I actually was already on a school board, and I asked the university, can you tell me who else there is who identifies as any one of them? Queer, transgender, LGB, anything? So there are about 555-ish advisory board members across the University of Pennsylvania, and there were five of us, just five of us. There’s been a lot of progression and change, but we, the five of us, thought, ‘You know, we need more of us.’ We talk to students, we engage with them, and we engage with the university.

Snyder Bulik: Why is it important for you to be visible?

Lau: Being visible and speaking about it is important, and that’s what carries for me. It’s been a principle for me for a while to just be visible. Someone else might not identify as LGBTQ, but they might identify as Black or immigrant or adopted or whatever it is, or having challenges at home. And that it’s OK to have challenges that are inherent to one’s self or have challenges that have developed over time.

Trying to compartmentalize it requires tremendous effort and energy, and it’s naturally distracting. And we don’t want to add those additional pressures. Drug development is already hard. Developing your people and being a good manager is hard. Making sure you get your expense reports and conducting the experiment, and thinking through the right design is hard. We don’t want our place of business to make it any harder than that. It’s really a tough job. So I talk about it on anyone’s first day of employment, and we talk about it at the workplace. It’s not always the most comfortable. But I like to think it helps. I like to think it helps people just bring themselves as they are to work.

Snyder Bulik: Was it your personal experience then that brought you to that kind of business philosophy?

Lau: It takes effort to be something other than who you are, to make an effort to shade or hide or not bring your natural, normal, beautiful self to work. That takes energy. And we don’t want 90% of your energy or 80% of your thought processes — we want it all, and we want you to feel fully engaged and interested and part of the community.

Sometimes people are very different, with very different viewpoints and different beliefs. But being able to do that, I think, is incredibly important, at least for our company. I’m very open about that, and I talk about who I am and what I do outside. And frankly, in my life, I did also hide parts of that. And it’s draining. It takes a lot of effort. You forget who you’ve said what to. And that wasn’t beneficial to the company that I was trying to lead. And I said I’d never do that again. — Beth Snyder Bulik

- Name Ramsey Johnson

- Company OUTbio

- Position Founder

Eight years in the making, a reflection on bringing together biotech’s LGBTQ community

While closing out clinical trials for a biotech startup that didn’t quite work, Ramsey Johnson looked for a way of networking to find his next role. Other industries had dedicated organizations for the LGBTQ+ community, but the life sciences field didn’t. So, in 2015, the clinical research veteran reached out to some of his peers and said he’d host an event. About a dozen people showed up.

The LGBTQ drug development meetup group, now known as OUTbio, was followed by event after event hosted by biopharmas looking to grow the community. The nonprofit has grown substantially since its launch in Boston, with outposts in California, New York, Ireland and elsewhere.

Endpoints News talked with Johnson in April about OUTbio’s formation story, lessons learned and future steps. The following Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Schloesser: What would you say are some of the biggest lessons you’ve learned when getting this off the ground and expanding it to where it is now? Were there any big lessons you learned or any event or encounter that stuck with you?

Johnson: I give advice all the time to the folks that are starting up these other branches. Because they are essentially where I was eight years ago, and I didn’t have anyone guiding me at the time. And what I see from them consistently is they all have these great ideas of the things that they want to do. I mean, they see us doing our events, and having a scholarship and having our mentor program, and they want to do all those things. I think my advice to them — and I wish I had thought of this more than eight years ago — is don’t run before you can walk. I mean, don’t try and bite off too much early on. There’s no pressure on you.

I said this the other day to somebody. I said, ‘You’re not curing cancer, right?’ You may have people in your database that are truly curing cancer, scientists that are trying to cure cancer, but you as an organization — OUTbio whatever, San Diego, Bay Area — you’re not curing cancer. So don’t put pressure on yourself to become something before you’re ready to do it. Take your first year, two years, three years, to become the best organization you can be at having events every month, having events every other month, or building your mailing list.

Schloesser: Is the plan to keep OUTbio a nonprofit? Or is the possibility open to sort of converting that and pursuing it more full-time?

Johnson: No, it’s never been something we’ve thought about or discussed, at least in my mind. I don’t want to speak for the board, but I’m pretty confident that everyone’s on the same page. They all see us remaining a nonprofit, and really our mission is to give back to the LGBTQ community and the life science community.

Schloesser: Next year, we have the 2024 election coming up. With some of the things that we’ve seen with certain bills being introduced and/or passed, is it within OUTBio’s purview to address these?

Johnson: We’ve not previously addressed, in a major public way, our stance on a lot of these issues. It certainly comes up in remarks that are made during events or things like that, but we’ve tried to stay out of the political arena a little bit. As we’ve gotten bigger and more well-known, I think the pressure is on a bit more to endorse candidates or put your weight behind certain movements or bills. And I’m certainly not opposed to that. It becomes difficult when you are a single person representing an entire organization. I have my opinions. And I have things that I would like to say, as a gay man and as a person, but I’m very wary that OUTbio is not necessarily mine anymore — it’s taken on a life of its own. And I don’t want to say something that impacts negatively on the organization as a whole.

But that being said, I think there are certainly things happening right now that impact not only the LGBTQ community but also potentially the life science community, as well, like what’s happening with the Plan B pill. So at a certain point, we’re probably going to have to make our stance on that known because it affects — it has a direct impact not only on the drug development industry but also potentially on marginalized communities. So women, and the LGBTQ community, the trans community. So there are certain things we probably will have to weigh in on. — Paul Schloesser

- Name Susan Whitehead

- Company PACT Pharma

- Position President and chief operating officer

Deriving power from being authentic

For all her years of experience in drug development, much of Susan Whitehead’s understanding of the shortcomings of the healthcare sector comes from her experience as a patient.

Whitehead is half-Asian and half-African American, with additional ethnic heritage. When she was diagnosed with a medical condition, she remembers “immediately being thrown stats” about how African Americans tend to do poorly — but not given a good explanation of why, despite her asking.

“It really just came down to two things,” she said. “One is lack of data because of the lack of diversity in clinical trials. And then, without an understanding of my background, there were some assumptions there — ‘well, she doesn’t know’ — or just putting me in a bucket.”

Health equity is key to Whitehead’s mission as she moved through a variety of roles in biopharma, spearheading regulatory filings, building out internal processes and, at one point, leading a global access program for a contract service provider.

Questions about diversifying clinical trials are also becoming particularly relevant at PACT Pharma, where she’s president and chief operating officer, as the biotech has downsized and pivoted to focus on applying its technology for personalized cancer therapies on treating cancers associated with HPV — which tend to impact underrepresented minorities.

Cell therapy, she acknowledges, is not inexpensive. But she also believes it’s worth trying to push ahead and overcome the supply chain challenges in scaling so they can one day reach underprivileged groups.

Whitehead, who went to college aspiring to be a social worker, said she fell into biopharma after taking a chemistry class and finding it could still align with her desire to help people. But she also realized she didn’t love being in the lab all the time and quickly switched to project and program management a few years into her career.

Although she developed a knack for operations and problem-solving, she said she “played it safe” to avoid the spotlight — until she came out in her 30s.

“If you think of a sports team like basketball, you have your five starters on the court,” she said. “I was really good at being the sixth person.”

Her career accelerated after coming out, a process that occurred after conversations with an openly LGBTQ female colleague.

She also thinks back on advice from her executive coach who, in response to the fears she shared about working for a new CEO, told her the boss didn’t care about the things that she thought could be holding her back; “he just cares if you make him look good.”

Once she started speaking up, Whitehead found that being a woman of color and also being out drew people to her who didn’t have the courage to share certain information with other top leaders. It put her in a position to take the concerns or feedback and share them anonymously with the management team.

“I was just lucky enough to be at organizations that really thanked me for that,” she said.

Having raised funds for HIV research and volunteered with LGBTQ and cancer advocacy groups in the past, Whitehead recently got involved with Biotech Amicus Effort. The group aims to rally biotech leaders to voice out on certain legal or political issues, such as the court fights around limiting the FDA-approved use of the abortion pill, mifepristone, or state laws restricting LGBTQIA+ rights.

“There’s not a whole lot of diverse leaders out there that kind of check those boxes,” she said, adding it’s important to pay it forward. Her advice for mentees? “Number one, to be really good at what they do. And number two, to be true to themselves and to take your seat at the table. I wish I had started to do that sooner.” — Amber Tong

- Name Paul Hastings

- Company Nkarta

- Position CEO and president

Being vocal = A good, accidental recruiting tool

You’ve probably heard from Paul Hastings before. Or know what he does. He speaks out often. And he doesn’t shy away from issues like gun control, abortion, diversity in clinical trials and LGBTQ rights.

The Biotechnology Innovation Organization chair strolls the halls of his Bay Area biotech, Nkarta Therapeutics, regularly to speak with employees about issues they care about. He worries that society will drift backward if people like himself don’t continue to push for change.

“I talk to people and say, ‘Hey, I’ve spoken out about this, I’ve spoken about that, are there things that you’d like me to speak out for you for?’ And it’s pretty amazing the responses I get,” Hastings said.

The decades of advocacy — he came out in pharma in the 1990s while at Genzyme — have elevated him to the point where people looking to join Nkarta are already familiar with his voice.

“We have people that come here for interviews that say, ‘Oh, we don’t need to meet Paul, we already know Paul, we’ve seen him on social media, he defends a lot of things, and my CEO doesn’t do that. I’m really interested in coming there because of that,’” Hastings said. “It actually is a recruiting tool. I don’t use it like that, but it has that ring to it for folks where they realize that I’m willing to do these kinds of things. To me, it’s just part of my activities of daily living, whether it be my neighborhood in San Francisco, on the national stage or on the international stage.”

Endpoints News caught up with Hastings in early April. Below is a Q&A edited for length and clarity.

LaHucik: Was there a particular part of your upbringing or early days in industry that really drove your advocacy?

Hastings: I’m a patient advocate because I was diagnosed with Crohn’s since the time I was 13 years old, and I learned at a very young age not to accept what I was told because it was an adult or a doctor or somebody with authority or power. It was my body that was going to be intruded and have surgery on or have procedures, and I learned to stand up for myself. Then in the 80s, when I was first at Roche, we were developing Alpha interferon for HIV, for AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma, and that’s where I met ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), and that’s where I watched them advocate for HIV therapies in the 90s. The learning from that helped me to advocate beyond just the groups like ACT UP for equality for LGBTQ folks, but also to reach out more broadly. Once I left the world of Big Pharma in the 80s and came into biotech and realized that biotech was full of very smart, very scientifically-focused people that tended to be very open-minded, it made it easy for me to feel comfortable and to start exerting some of my influence.

LaHucik: Has the tight financing environment for biotech had an impact on companies’ diversity commitments or backing for employee resource groups as it relates to LGBTQ groups or other DEI initiatives?

Hastings: I haven’t seen that. I would be disingenuous if I didn’t tell you that we have discussions at the BIO board all the time about what does BIO want to advocate for. I have to distinguish what is funded by an organization that wants to advocate for certain things and what is something that I need to do as a person or to get other people to speak up as persons to do, but I haven’t really seen a reduction in DEI initiatives.

It’s in everyone’s best interest to continue to push for these things, no matter how much one side or another accuses us of being a ‘woke,’ or as I would say, ‘awake and not asleep at the switch,’ so I think that the push on these initiatives by people who really advocate for it and want to use their leadership to help advocate for it has not slowed these initiatives down.

LaHucik: What’s next for you personally?

Hastings: I’m proud to say I’m 63. I feel like I’m 45. I have a lot of juice left, and I love what I do. This is my sixth company. I’m in this industry for the long haul. I just had dinner with a friend Saturday night, and he said to me, ‘I’m done. This industry is now all about financial engineering. It’s all about saving our way to whatever the next date is when the market comes back, and where’s the focus on patients gone?’ And I said, ‘Right here — I’m still here. I’m not leaving. And it’s OK if that’s your decision that you happen to be more involved on boards and hearing investors talk about what we need to do.’ But I still think we fight, we fight for patients and we fight for our industry and the place this industry has in the worldwide population. I’ll be doing that for quite some time.

LaHucik: The next presidential election is coming up, that campaign season, so talk about what you’ll be vocal about, what you’ll be advocating during that.

Hastings: I just argued with myself at the gym this morning about whether I should post Randy Rainbow’s song that he posted recently. He did a song [a spoof on Trump’s arraignment]. He did this mock interview of the former president and what he’s going through with his trials and what have you. My sister sent it to me. It was hysterical. I’m watching it on the phone this morning at the gym. Everyone’s watching me, and they see me laughing. And I was just thinking to myself, ‘Should I repost this, or should I not repost this today?’ On a more serious note, just watching what is going on in our country and watching what’s going on in Israel right now, I’m scared. I’m scared that we’re going backward. We took away rights that we gave to women 50 years ago. Elections matter because those things tend to eke out of elections.

I’d like to get back to the days of moderation when people from both sides of the aisle talked to each other, worked together, have differences but acknowledged them. I think that’s really, really, really important. So one of the reasons I didn’t repost Randy Rainbow’s little funny thing this morning was because I didn’t want someone to say, ‘Oh, here he goes again.’ — Kyle LaHucik

- Name Celia Sandhya Daniels

- Company Rebekon Consulting

- Position CEO and founder

Clinical trial diversity and trans rights in biopharma

Celia Sandhya Daniels grew up in the southern part of India in the 1970s. The first time she came out to her mom as a kid, her mom told her, “You’re a boy — you’re not a girl,” Celia recalled. “That was the only answer she gave.”

Later on, Celia worked on the first human genome project in India while getting her master’s in computer science, and then moved to the US to work for various life science companies. Many years later, in 2017, she decided to come out as Celia to her co-workers.

But after transitioning, Celia noticed it was difficult to find new jobs. “Accenture offered me a job without even an interview because they knew how good I was before I transitioned,” she said. “But after I transitioned, I reached out to all these companies and said, ‘Hey, I’m available, and you know, I’m the same person.’ And none of them responded back.”

“They didn’t want to hire me because they didn’t know how to hire me,” she said.

So instead, she took her daughter’s advice. “When I came out, she was 12 years old. She told me, ‘Why don’t you start your own company?’” Celia said. “That’s what became Rebekon Consulting. And I went to my clients, and I said, ‘I want to consult with you.’ They were willing to now open their positions because I was coming in as a consultant, so they didn’t have to carry the extra baggage.”

As a management consultant, she has worked with companies like Amgen, Gilead and Genentech, but a major part of her work now is advocating for LGBTQ+ rights. “I educate companies,” she said. “How do you not just recruit but also retain the LGBTQ community?”

“And in the health equity space, one of the issues the LGBTQ folks face when it comes to clinical trials and when they brand a medicine, they always show a heteronormative family — husband, wife, children, right? Only when it comes to HIV do they show a gay couple. But when it comes to other medicines, why can’t they show LGBTQ patients?”

Celia thinks biopharma companies can do much better. “I challenge any pharmaceutical company to come and tell me that they have really made a change across patient diversity in clinical trials for trans patients. Not for a trans-oriented drug, but for any drug.” — Lei Lei Wu

- Name Martin Chavez

- Company Recursion

- Position Chair

Biochemistry to banking to life sciences’ computational future

While former Goldman Sachs CFO Martin Chavez was once the most senior openly gay executive there, the way he describes himself is always as a computer scientist.

And he’s used those computer science and biochem chops to navigate his way into the center of the life sciences industry after spending decades on Wall Street.

Writing via email, Chavez explained how he felt this urge to enter the life sciences industry back in 1981 when he got to Harvard, and the legendary professor Steve Harrison of high-resolution virus crystallography fame, told Chavez: “The future of the life sciences is computational.”

“How prescient was that? I majored in biochemistry as well as computer science, then studied medicine and computer science as a graduate student at Stanford,” Chavez said.

After retiring from Goldman and more than 30 years on Wall Street, Chavez told the Wall Street Journal: “The next frontier is making life — genes, cells, organs — programmable.”

And since then, he’s sought to do just that, working with companies such as Recursion, Datavant, Mammoth, Earli, and Cambrian.

As far as any struggles to break into the biotech industry because of his sexual orientation, Chavez said, “I haven’t encountered any challenges that arise from my being gay. I’ve made my way by working with companies who have been indifferent to my sexual orientation. As companies have worked to become inclusive, not just indifferent, all of us have reaped the benefits.”

But Chavez acknowledges that the biotech industry still isn’t a very diverse one overall.

“Industry, in general, has a diversity problem,” he said. “Across the board, companies have worked to make their entry-level reflect the demographics of the places where they operate. Unfortunately, that’s not enough: The senior ranks will remain less diverse unless and until companies actively work to give coaching, mentorship, sponsorship, and equal opportunity to historically underrepresented groups.”

He also made clear that he doesn’t think people should wait for this change before breaking down barriers.

“Many young people from diverse backgrounds tell me that they’ll believe in their possibility of success when they see a successful person who shares their background,” Chavez said. “If I had been waiting for a Hispanic and LGBTQ+ leader on Wall Street or in Silicon Valley, I’d still be waiting. I’ve sought and received the sponsorship of great leaders, who were generally straight white men, and that has made all the difference.” — Zachary Brennan

- Name Jayson Johnson

- Company Genentech

- Position Head of diversity & inclusion business partnering and learning & development

Moving from the ballet stage to big pharma

After spending most of his career in dance, Jayson Johnson tiptoed into an unfamiliar industry six years ago. Now he’s choreographing Genentech’s diversity and inclusion efforts — and he couldn’t be happier.

The former dancer spent about seven years in fundraising at The Washington Ballet in DC and the San Francisco Ballet and was also on the board at LEVYdance. In 2017, he joined Roche’s Genentech as senior talent discovery partner.

“I had a pretty eclectic background. I’ve always loved the performing arts,” Johnson said. He started playing the saxophone in fifth grade, sang in his high school choir, and later studied under Katherine Dunham, a famous modern dance choreographer. When he decided to leave the nonprofit world, and after eight years in fundraising at Harvard University, Genentech was “a very easy sell.”

“It was very important for me to go someplace that had a strong mission that I could get behind,” he said. “We are doing now what patients need next,” he added.

In January of last year, Johnson was promoted to head of D&I business partnering and learning and development at Genentech. His teams help shape D&I programs, plan training on topics like unconscious bias, allyship and microaggressions and have established an inclusive hiring certification process.

“My team inspires our industry-leading changemakers to really embed diversity and inclusion in every aspect of their work,” he said. “So it’s not just an add-on; it’s actually interwoven in through their day-to-day work.”

Johnson is also a member of the company’s gPRIDE organization, which facilitates events and programs to establish “a sense of belonging for all employees, no matter what their backgrounds are.” The company’s benefits team also houses a variety of LGBTQ+ resources, including an extensive gender transition support system.

Outside of work, he’s a commissioner on the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, on the board of trustees at the San Francisco Ballet, and an active member of several committees at his alma mater, Washington University in St. Louis. He’s inspired, in part, by his family, who were supportive when he came out in college and continues to be “amazing champions of me and the work that I do and what I represent.”

“When I think about diversity and leadership, it takes time to cultivate that leadership. So that’s why it’s important to invest in leaders of tomorrow,” he said. “When I look around the industry, I see baby steps as well as leaps and bounds being made by organizations to really change the way we approach the work, the way we think inclusively.” — Nicole DeFeudis

- Name Mira Chaurushiya

- Company Westlake Village BioPartners

- Position Managing director

Venturing toward a time when sexuality is the ‘least interesting thing’ about oneself.

Mira Chaurushiya used to think being part of the LGBTQ community was the “least interesting thing” about her. She’d like that to be the case again.

But more work has to be done on LGBTQ+ inclusion in biotech and broader society for her to feel comfortable with that return. With close to a decade under her belt as a biotech venture capitalist at 5AM Ventures and now Westlake Village BioPartners, Chaurushiya focuses her time on helping the next generation build new drug development companies, whether by investing in them or serving on the board of Nucleate, an organization helping life sciences entrepreneurs find their footing. Prior to investing, she spent most of the 2000s and early 2010s at research institutions like Rockefeller University, the University of Chicago, the Salk Institute and then industry at Genentech.

The following Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

LaHucik: We spoke about a year and a half ago about being LGBTQ in biotech. We both changed jobs since then, so talk a little bit about what you’ve been up to since then. What’s it been like at (Los Angeles-area venture firm) Westlake so far?

Chaurushiya: I grew up in LA. I’ve lived all over the country, and worked in labs all over the country. I have never worked in LA, and that’s not because I have any aversion to my family. Quite the contrary. I just didn’t believe that there was a career and an ecosystem to function in the biotech space in Los Angeles. And when I met Beth [Seidenberg, Westlake founding managing director] and she convinced me to come down and see LA, really seeing the infrastructure that had been built, Westlake’s role in catalyzing various parts of the ecosystem from talent to infrastructure, to financings to company-building expertise come together was really compelling.

[Beth’s] obviously a legend in our ecosystem and a person I felt like there’s a ton to learn from alongside building the firm and ecosystem.

It was a little bit of a leap of faith because these things live or die by the relationships with the people around the partnership, but it’s been great so far.

LaHucik: This special report is focused on LGBTQ leaders. Last time we spoke, you had talked about changes in the industry. Have you seen any additional changes since that point?

Chaurushiya: Maybe frustratingly not. When we talked then, I was in a mode of, “I think there has been a lot of progress,” and I still believe that. Maybe the rate at which the progress is accelerating is not as high. Maybe that’s to some extent reflective of progress we’ve made as a community, but I think there’s still a ways to go. From the Westlake perspective, when you look at the managing directors at Westlake today, of the four of us, two of us identify as LGBTQ. That’s pretty rare. I can’t imagine any other biotech firm where the leadership has that kind of representation. I used to think being gay was the least interesting thing about me. I would love for this to become so common that it once again becomes the least interesting thing about me, but I just think we’re really far from that right now.

LaHucik: What are some key areas that you think people in biotech can work on and broader society can do?

Chaurushiya: A number of junior people have come to me, and they’re much earlier in their journeys of whether they want to come out, how they’re feeling about their own LGBTQ status, so being a person that people came to to say, “Here’s what I’m doing. Here’s what I’m thinking. Here’s what I’m reevaluating, and how do I integrate this on a personal level and how do I integrate this on a professional level?” That has been a good outcome. But separately, the fact that so many came forward and they confided in me, but a year later, they still have not told anyone else, that’s been surprising. They’re working at different places than I work at, but they are in the biotech industry, so I feel that’s one of the indicators we still have some work to do just to make people feel comfortable, and that they can be their authentic selves at work.

LaHucik: With the finance environment where it is, are startups pulling back on DEI initiatives?

Chaurushiya: I haven’t seen it personally, but I can absolutely tell that if you are in a reactive mode and you are trying to finance a company or you’re trying to extend your runway or you’re blocking and tackling through tough clinical readouts, that these are things that can very easily fall on the wayside. I haven’t personally seen it at our companies. But I would caveat this as being LGBTQ is a non-visible type of diversity. The representation at a company or in an organization is as visible as people want themselves to be, and so it’s an incredibly difficult metric to track if people aren’t willing to tell us who they are.

LaHucik: Are there any other organizations that you’ve gotten involved with in LA or any from San Francisco that you want to highlight?

Chaurushiya: I’m involved with Nucleate, which is a nationwide organization [focused on biotech entrepreneurship]. I’m on the board there. Diversity is something we talk about a lot, and the conversations have been more around gender diversity. When you don’t pay attention to this type of diversity and you let things happen organically, you wind up where you will get one female around a table and that person will call you and say, “Kind of interesting, a year into this, we don’t have the diversity we want.” It does have to be forefront of mind.

LaHucik: When do those conversations happen, bringing it to the forefront of mind?

Chaurushiya: From the earliest stages. You’re evaluating the team on their complementary skill sets, and how well they work together. How do they work together? Where is one person’s superpower, and where’s the other person’s? They should have different ones. We’re also looking for diversity because diversity of background, and diversity of experience means diversity of opinions at the table, which by definition gives you more optionality to consider. When you look around a table and everybody looks the same, and everybody talks the same, and everybody’s been in the same places, you are not going to get the diversity of experience that drives innovation. We’re always trying to innovate ourselves out of sticky situations in biotech, whether it’s technical, whether it’s strategic, whether it’s operational execution. If you have a bunch of the same people around the table, they’re all going to give the same idea, and it’s usually an idea they tried in the past, and you need a new idea. — Kyle LaHucik

- Name Greg Vladimer

- Company Exscientia

- Position VP of translational research

Founding a company and serving ‘dual roles as managers’

Greg Vladimer has made it a point to create a safe, accepting and diverse community at work — first as co-founder and CSO of precision medicine biotech Allcyte, acquired by Exscientia in 2021.

As Exscientia’s VP of translational research, he’s made sure the inclusive environment he fostered at Allcyte moved over to its new home. That entails support systems, mentorship and project ownership as the team works on functional and deep learning, omics, complex biomarker discovery and preclinical data for target discovery.

It all began when Vladimer moved to Austria for a postdoc on translational immunology using systems biology approaches.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lewin: Talk a little bit about how you create networks and links amongst colleagues in the LGBTQ+ community.

Vladimer: EDI surveys are great. They can place you and your company and where you stand on a map of diversity and inclusion within your company, but what’s nice about Exscientia and what’s nice about the community here is that it goes one step further. It goes into small things like Slack channels, where you have an LGBTQ+ community of scientists that can communicate, and those are public channels. There are private channels where we can help each other if there is a misstep or someone needs advice from somebody with a similar background to overarching acceptance of the community amongst the people that we are hiring.

Lewin: These are really challenging roles that take a lot of brainpower and focus. How do you stay focused and inspired with work?

Vladimer: I think we play dual roles as managers, especially in a diverse environment. We need to execute on the goals of the company, and we are here as mentors. Ultimately, if we let unfortunate news cycles or unfortunate political decisions sway the boat, they can cause ripple effects. I think our jobs ultimately require us to look at political events, especially that target the LGBTQ+ community in general, and be able to look towards the bigger picture and work together to fight back against those policies. We can do that through successes within science, within media, and within the public environment to show that members of the LGBTQ+ community that might be the target of these changing political backgrounds can still be successful.

Lewin: If you had someone come to you, whether part of the LGBTQ+ community or not, who was moving into a management role, what would you recommend to them to create the same environment that you’ve made?

Vladimer: One, foster mutual respect for colleagues. This is mandatory. And two, it’s to enable decision-making, and it’s to enable decision-making at all levels where you have ownership of projects and ownership of workflows, no matter what they are, with the people who are actually doing the execution of this. Our jobs as managers are to push the train in the right direction, but ultimately the speed and the decision-making power come from the people who are in the laboratories or who are at the computers doing the work. — Katherine Lewin

- Name Peng Leong

- Company BioAge

- Position Chief business officer, head of brain aging

Infusing quality into our later years with therapeutics to curb aging-related diseases

Peng Leong wants to help us live a better quality life in our later years.

The three-decade industry veteran — who’s gone from scientist roles to investment banking to business development to the C-suite — is part of the growing field of biotech startups trying to tackle aging-related diseases.

He’s “deep into the science” and routinely finds himself combing through the dataset at BioAge, a California upstart looking for new drug targets for chronic diseases with the assistance of millions of data points across thousands of patients.

“Of course, all of us, when we get older, we want to have healthy bodies and minds, as well, so that we can have a great quality of life into our old age, so our dataset also allows us to look at cognitive decline as people age,” Leong said.

The biotech is gearing up for Phase II trials of an ex-Amgen drug candidate, now dubbed BGE-105. BioAge expects to start enrolling patients this summer to investigate the drug’s potential to prevent ICU diaphragmatic atrophy and critical illness myopathy, and then another study next year for muscle preservation during GLP-1 therapy for older adults who have obesity, Leong said. Preclinical efforts are also investigating an NLRP3 for neuro and ocular inflammation and another APJ agonist for undisclosed brain aging conditions.

Leong is head of brain aging at the 60-employee upstart. The title is a rarity in the industry but is attached to one of his other hats, the role of chief business officer, which is a position he’s held at Shasqi and Kazia Therapeutics previously. Between those, he was strategy chief for a brief stint at Engine Biosciences.

His career began as a scientist at Chiron prior to the 2006 Novartis deal. He moved into investment banking shortly before the financial crisis, during which he worked on healthcare IPOs, M&A and other financing vehicles for Piper Jaffray’s clients. In the midst of that, he adopted his son, who’s about to enter high school. He then worked on a drug royalty fund at DRI Capital, led Asia-Pacific business development for Merck KGaA out of Singapore (where he was a little less open about his sexuality because of regional laws) and then transferred to the startup world in the mid-2010s.

Throughout that time, he’s seen firsthand the expansion of the LGBTQ community within life sciences.

He recalls attending his first holiday party at Chiron in the late 1990s with his then-partner, now husband, and telling colleagues that the man beside him was his roommate.

“Later on, people said, ‘You know, it’s obvious he’s not your roommate,’” Leong recalled. “‘It’s absolutely not an issue — you’re in the Bay Area.’”

In the early 2000s, when he’d attend the annual JP Morgan Healthcare Conference, there’d be only a couple dozen LGBTQ folks gathering for drinks at the organization of John Crandon, an outside general counsel to multiple life sciences companies.

But in the past few years, Leong said, it’s become more of an official event with JPM’s backing for a cocktail event that attracts hundreds of people. — Kyle LaHucik

- Name Joshua Cohen

- Company Braeburn

- Position Chief medical officer

Addressing healthcare disparities and bringing an opioid use disorder med to the market in September

“I was in my second year of medical school when I came out.”

Coming out as gay in 2001 was not easy, according to Cohen, now the chief medical officer at Braeburn.

“I didn’t know other people that were gay. Really, until I went to college, I had never met anyone who was gay. And even in college, I didn’t really relate to the people I met that were gay — I didn’t see myself in them,” said Cohen.

However, after he came out and saw a positive response, Cohen said he knew he had to get involved in the community — especially with disparities that he saw in the LGBTQ+ community, such as higher rates of depression, substance use disorders and suicide.

To that end, he got involved with the Trevor Project’s NextGen, a young professionals group in New York City that supported the Trevor Project, a crisis support nonprofit focused on young LGBTQ+ people. He eventually became co-chair while he was still in practice.

“And we were raising money for Trevor Project, doing all sorts of programming, really engaging with the community to try to really tell stories of hope for young people in support of that organization’s mission,” Cohen said, adding that it “was a really amazing experience, got me involved in the LGBTQ advocacy world.”

Cohen started out as a practicing neurologist at Mount Sinai before pivoting to his first biotech foray at Teva, where he worked on now-approved migraine drug Ajovy. Outside of his daily work, Cohen is a board member of the American Medical Association Foundation.

When he got started at the foundation, Cohen formed a fundraising effort to look at and address healthcare disparities for LGBTQ+ people. The project expanded into fellowship training for doctors to focus on the community’s health needs.

The impact can be seen in fellowship programs at Harvard, Vanderbilt, Mount Sinai and the University of Wisconsin.

At Braeburn, Cohen advocates for the LGBTQ+ community as the executive sponsor for the Pennsylvania biotech’s diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging group, which it calls BraEDI. As medical chief, Cohen leads work on an opioid use disorder med, a long-acting form of already-approved opioid dependence drug buprenorphine. The FDA approved the med in May as Brixadi for moderate to severe opioid use disorder. This comes more than two years after the FDA issued a CRL for the drug in 2020, citing manufacturing deficiencies.

The company originally in-licensed the molecule from Camurus, a Swedish biotech that developed the molecule, in a $151 million deal in 2014 — and Braeburn gets exclusive rights in North America.

Cohen said Braeburn hopes to have the drug, which can be given in either a weekly or monthly injection, available by September.

People who suffer from opioid use disorder also face a lot of health disparities — especially more so in historically marginalized groups, Cohen noted.

“That certainly affects people of color; it affects the LGBTQ+ community. And so we’re very thoughtful in how we engage with the community of patients that we’re trying to help,” the medical chief added.

Cohen also touched on some of the anti-LGBTQ laws being introduced in many states, calling it “the greatest attack on the LGBTQ+ community since the ’80s.” And while the chief medical officer said it is a tough thing to solve, “we’re going to do whatever we can to continue to support that community, regardless of what goes on.” — Paul Schloesser

- Name Amit Rakhit

- Company Flare Therapeutics

- Position CEO

Progressing corporate tax policies, igniting a Third Rock cancer startup

Amit Rakhit was chatting with two top Biogen executives about a decade ago when he brought up something that, to him, was a matter of fact.

Although Rakhit, then a vice president of program leadership and management, supposedly earned as much as other VPs at the company, he had to pay more federal tax on the spousal benefits his husband received — because he’s in a same-sex marriage.

“Initially, I didn’t think much of it,” he recalled. “It was what it was.”

But it was news to Steve Holtzman and Susan Alexander, Biogen’s executive vice president of corporate development and general counsel at the time, respectively. The conversation set in motion a move for Biogen to offset the difference by reimbursing gay employees for the additional taxes until it was no longer necessary.

It was one prominent example of Rakhit’s longtime involvement in initiatives to make everyone feel welcome at the companies he helped lead. After moving from Bristol Myers Squibb to Biogen — then a smaller player with around 2,000 people — he spearheaded the creation of a new LGBT employee resource group to review and drive internal changes.

Now, as the CEO of Flare Therapeutics, he continues to keep up with issues of the day with the biotech’s diversity, equity, belonging and inclusion, ensuring HR policies are not hampering employees’ ability to bring their full selves to work.

“Sometimes these seem to be small changes, but they can have meaningful impact,” he said. “Not everybody thinks about those because they don’t have to, right? But for the person that it matters to, that’s really impactful for them.”

Growing up in California, Rakhit counts himself fortunate to feel supported as he came out at 17 years old. Throughout his medical training at Tufts Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and as he moves through his biotech career, he’s remained “fairly open.”

“That whole coming out process and being comfortable with who you are gives you a resiliency, a kind of inner strength that you carry forward,” he said.

At the same time, it also meant becoming sensitive to bullies and outsiders — while taking a stand and speaking up for those who don’t have a voice. Outside of work, he volunteers and supports groups like Human Rights Campaign and the Trevor Project, which he believes could be better positioned to take action on addressing political or legal attacks on LGBTQ communities.

For Rakhit, Flare’s investment in diversity and different perspectives is paying off directly in the biotech’s work, bringing together “super-smart” people from industry and academic backgrounds who he said are both passionate about the work and each other. Flare’s lead program is slated to enter the clinic just 18 months after discovery, and the Third Rock-backed startup, which is developing cancer drugs that target transcription factors, recently closed a $123 million financing round with participation from Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Novartis.

“The diversity piece and the people piece are the underlying substrates, the underlying foundation of what makes the company able to reach those goals that we set for ourselves,” he said. — Amber Tong

Editor’s note: This profile has been updated to correct that Rakhit went to Tufts Medical School, not Harvard Medical School.

- Name Coy Stout

- Company Brii Biosciences

- Position SVP, head of patient advocacy & policy

Forging a new path after ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’

Nearly 30 years ago, Coy Stout vowed never to compromise himself for his career.

Stout intended to join the military after shifting from an undergrad pre-med track, enlisting in the Air Force ROTC. But when former President Bill Clinton instituted the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the mid-1990s, Stout — who said he came out as gay in college — decided to change paths again and pursued a career in social work.

“Once I came out, I decided I’m out,” Stout said. “I’m not going to compromise who I am to get a job or be accepted for only part of my identity.”

That choice led to Stout’s successful career in healthcare, first in the nonprofit sector and then in biopharma. Feeling a “social justice calling” after dropping out of the ROTC program, Stout found a place at Whitman-Walker Health, one of the country’s oldest LGBTQ+ health clinics in Washington, DC, where he was at the forefront of the HIV epidemic.

His time at Whitman-Walker gave him the experience needed to help advocate for patients, he said, as he learned how to get people enrolled in clinical trials and partner with drug companies working with them on community outreach. It was also the first time he considered the possibility of working in pharma, he said.

“I saw how the medications that were being developed for HIV transformed it from almost a guaranteed death sentence into a chronic, treatable disease and now a preventable disease,” Stout said. “That really opened my mind up to how pharmaceutical companies advanced healthcare and research.”

He soon jumped to working for the Maryland state government as head of their AIDS drug assistance program, where he continued fostering relationships in the industry. And those ties eventually landed him a gig at Gilead, where he spent 17 years on the commercial side, focusing on coverage, reimbursement and designing patient access programs.

Stout said he both received support and faced resistance throughout his career. Older coworkers who hadn’t come out would privately thank him for serving as a role model, whereas some bristled at having to work for a gay manager. Stout, though, is thankful for the growing acceptance of LGBTQ+ people since the 1990s.

“As painful as ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ was, it did start a very important conversation around public service and being gay. That had never happened before,” Stout said. “There’s definitely been an evolution where more value has been placed on being out and being gay in the workplace.”

Now, Stout works for Brii Biosciences as a leader in its postpartum depression advocacy strategy. He also joined a mentorship program at OUTbio, a biopharma industry LGBTQ+ professional group, where he was recently matched with his first mentee. Stout said he’s excited to learn about the experiences of younger LGBTQ+ folks in biopharma. — Max Gelman

- Name Allene Diaz

- Company Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Mersana Therapeutics

- Position Director

Breaking a self-imposed silence

Allene Diaz recalls helping rate top executives for a yearly raise while on the assessment committee for a company. Two candidates were high performers but had both received some pushback on the way they did things. The committee gave the man a higher rating than the woman. Diaz was sure to point that out.

“Years before, I would have been quiet. I was like, wait a minute, this other person, who was a male, ticks a lot of people off, yet he got a stellar rating on how he did things,” Diaz said. “But the woman delivered the same amount and ticked people off, but she got in the middlebox. That is not fair.”

For many years of her career, she said she might have been quiet in situations like that, including around her own life. Over the majority of Diaz’s career, she was careful to keep her private life extra-private — using neutral pronouns for her partner and avoiding discussions with her colleagues about how she spent her weekends.

Growing up in the South, raised by a conservative, Catholic, Cuban family, she had been told to keep her personal life “invisible.”

That is, until 2015 when her spouse joined her for a company event.

“I think what I have done, which is fairly recent for me, is starting to become much more visible as a member of the LGBTQ community,” Diaz said. “I started working in the pharmaceutical industry in 1987, and 2015 was the first time I brought her to a corporate event. So you can imagine how many years I was parsing my words very carefully.”

Over the last few years, Diaz has made an effort to tell her story more frequently.

That includes helping found the Boston WITH chapter in 2020. Comprising a group of leaders in the healthcare industry, WITH members make personal commitments to champion and advance people in underrepresented groups.

Diversity and inclusion are improving when it comes to the biotech industry, Diaz said. She’s fortunate to have worked for 10 companies over the last few decades where, over time, each one was more open and inclusive than the previous. She plans to continue to stick up for underrepresented people in her work and personal life and to continue to tell her story.

“If anybody was holding anybody back, it was probably me because of my own fear,” Diaz said. “I’ve never once when I have come out to anyone in the biotech or pharma industry, been treated with anything but respect, to be fair. So, I think that was a self-imposed silence.” — Katherine Lewin

- Name Jon Newton

- Company ICON

- Position VP of corporate development, innovative partnerships & strategic healthcare

Rugby, clinical trial diversity and OUTbio in Ireland

Jon Newton, a VP at Ireland-based contract research organization ICON, said his biggest accomplishment will be getting married in September.

Newton’s extensive career in the CRO space spans various leadership roles at PPD and PRA. But he has dealt with issues in leading teams in countries where LGBTQ people are not recognized or outlawed.

The experiences have encouraged him and his company to pursue more DEI initiatives and to expand work with both industry groups and even LGBTQ-aligned sports organizations.

Endpoints News spoke with Newton about his career and diversity efforts in 2023.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Patchen: What would you say are some of the biggest adversities you faced as an open man in this space?

Newton: I wasn’t immediately out when I joined the workforce. Coming out later in my career was a challenge because people kind of know you one way, and then you’re not your authentic self. As I evolved and moved into management, the size of my team grew. At maximum capacity, I was managing a region of APAC and Europe for 800 people. I was traveling to countries and managing individuals where homosexuality was illegal in some countries or, at a minimum, frowned upon. So, I did worry about the impact my sexuality might have on the team’s performance, as crazy as that sounds today, but I was always supported by managers.

We often say, “Well, maybe it’s difficult to be yourself at work, and when you leave the office, that’s when you can be yourself,” but sometimes the opposite is true. Maybe there’s only the safe space at work where they can be themselves in the four walls of the office, and then they have to go home to a family that isn’t accepting or a situation that’s not as open as we would like it to be.

Patchen: Can you talk about some of the organizations that you are involved with?

Newton: Moving countries, sports has been a great way to connect with people and get inclusive clubs on board. I joined the London Knights basketball and Emerald Warriors rugby [teams]. As you get older, you start to play less, but I found I stay involved through events and fundraisers. We just did a drag show with the Emerald Warriors rugby club, and we raised €17,000. I am of the seven co-founders who decided to start OUTbio in Ireland. So they had chapters in the US, the UK and now Ireland. So seven of us got together across the industry, Gilead, MSD, AbbVie, and ICON.

Patchen: Why did you start OUTbio in Ireland?

Newton: I got introduced during Covid. I had stumbled across OUTbio, and I thought the name was going to be cool; that kind of fit what we were thinking. So we reached out to the US branch and said, “What do you guys think about an OUTbio Ireland chapter?” And they were super-enthusiastic. We started in 2022 and have done five events so far in Dublin. We have 13 different companies and organizations of all sizes attending. Our last speaker was from HIV Ireland. We just got incorporated as a nonprofit, so that’ll help with the fundraising activities to sponsor the events.

Patchen: What is your perspective on the anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ legislation in the US?

Newton: We’re an Irish company, and Ireland, in general, is pretty progressive in terms of LGBTQ-plus rights. So we’re pretty progressive in Ireland overall, and that mentality permeates within the organization itself and sensibility trickles down. Ireland was the first country to recognize marriage equality by popular vote. I wouldn’t say Ireland is immune to the global trends that you’re seeing in the US and UK, but in general, we’re pretty OK as a country. As a company, I think ICON’s proudly Irish, and the leadership reflects a stance of positive support for the community and employees associated with that. We can’t control the politics of the world, but we can focus on the culture and what we can do for our employees within those four walls so they feel like they have a safe space. And they can be their authentic selves. And I’d say we hold employees accountable to those values. — Tyler Patchen

- Name John Davis

- Company Sonoma Biotherapeutics

- Position Interim chief medical officer

Urging for companies to be more vocal